by Vidagdha Bennett1

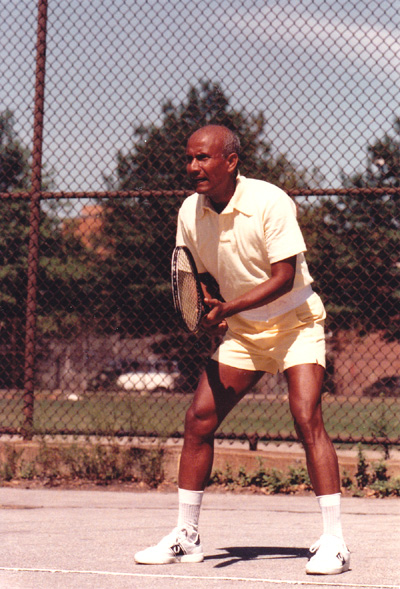

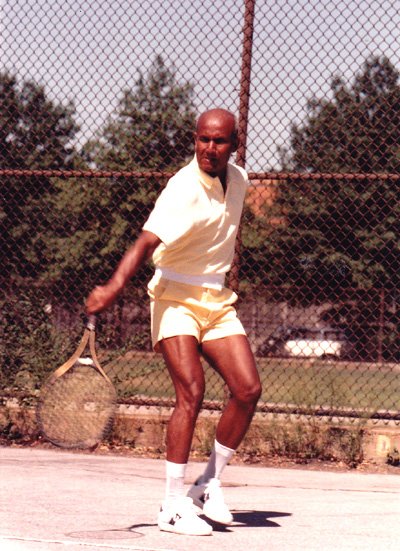

Watching Sri Chinmoy play tennis on a summer’s morning in New York, it is hard to believe that a little over four years ago the game was unfamiliar to him. Today, approaching fifty years of age, he moves about the court with the natural ease of one who has attained a sure and certain mastery of what must be one of the most demanding and skilled of sports. Sri Chinmoy’s strokes are smooth, even and powerful; his timing excellent; his rhythm relaxed. It is at once clear that a lifetime of dedication to sport lies behind the beauty and grace of his style.

In his early teens, Sri Chinmoy devoted many hours each day to becoming a champion sprinter. Extending his interests to the shot put, discus and javelin, he gained tremendous strength in his upper body as well as the ability to let his body flow into a throw in a single and continuous movement. In addition to these and other athletic events, football (soccer) played a major part in Sri Chinmoy’s formative years, the deft footwork and agility required providing a perfect complement to his innate speed.

So it was that at the age of forty-five years, when Sri Chinmoy first displayed an interest in tennis, it was not as an untutored sportsman that he approached the game but as an athlete of considerable talent in many areas, a man who had the speed to meet its challenge, who had the determination to master it, the will-power to endure and a unique spirit of sportsmanship which, in time, would signal a new approach to tennis itself.

Most tennis players, especially those who go on to become great, take up the game in childhood. Years of training and discipline go towards shaping and perfecting the classic tennis strokes of service, forehand, backhand, volley, smash and so on. It is generally held that if one learns as a child, the body is light and supple, the mind free from preconceived ideas of style and form. In later years, this early discipline ripens into a winning combination of skill and intuitive feeling for the sport.

In the case of Sri Chinmoy, who first began playing on June 13th, 1977 – at an age when other players might consider reducing their level of competitive sport – age, as such, did not prove a hindrance to learning the game, for his muscular body still retained its tremendous litheness and strength. More than any physical advantage, however, Sri Chinmoy brought to his new endeavour a wealth of concentrative power and the heart of a child. He came to it without having to unlearn old and binding habits, and with what can only be described as a boundless receptivity to all facets of the game. Coupled with this was his willingness to spend far more than the hours necessary to perfect his game. Openness, dedication, concentration and natural ability – these factors supplied the groundwork of Sri Chinmoy’s tennis.

Sri Chinmoy adopts the ready stance. Photo by Dhananjaya

Having taken up the game in June, Sri Chinmoy pursued his newfound interest wholeheartedly and, throughout the month of July, he played every day at least once on a concrete court. His partners at that time were several of his disciples who were already excellent players. They gave no lessons or theoretic instruction to Sri Chinmoy, however, for it soon became evident that his chosen method of learning was by actual on-court experience. By playing, he discovered how to play, and by playing better and better opponents, he gradually raised his own standard. Observing and absorbing the best qualities of his partners’ games, he grasped the fundamentals of the strokes and was able to perceive more clearly his particular strengths and weaknesses.

Sri Chinmoy then began to augment his learning process in various ways. On September 6th, 1977, and on several days following, he attended the U.S. Open Tennis Championships in Forest Hills. He also commenced practising with a ball machine that directed balls to him at different heights and speeds. He used exercise equipment to increase the size and strength of his right wrist, forearm and bicep. Some of this equipment was purchased; other pieces were designed at his suggestion so that he could avail himself of time spent travelling in a car or seated for long periods.

Because of the difficulty he experienced in hiring a tennis court during the hours that suited him, Sri Chinmoy learnt many of his skills off the court – on the street outside his home and in a low-roofed building, which he called “Progress-Promise”. When he had the opportunity to apply these skills in an on-court situation, Sri Chinmoy would spend hours at a time working through a range of shots, acquiring subtlety in his use of the racquet and developing a feel for spin.

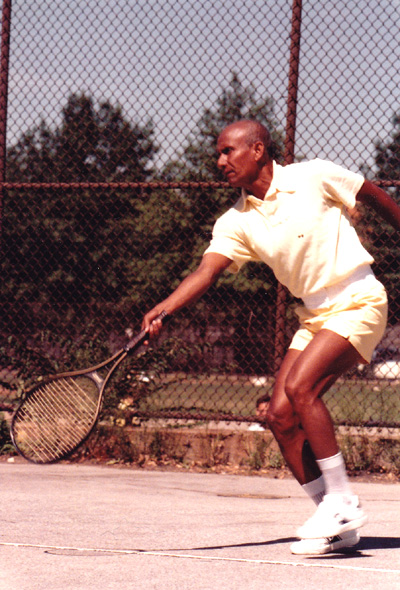

The graceful form that characterises Sri Chinmoy’s game. Photo by Dhananjaya

On September 17th, 1977, he won his first round at the United Nations Tennis Tournament, which took place at the Sterling Tennis Courts in Queens. Although he lost his match the next day, in the second round of the tournament, his progress demonstrated that in just three short months he had become highly proficient at the game.

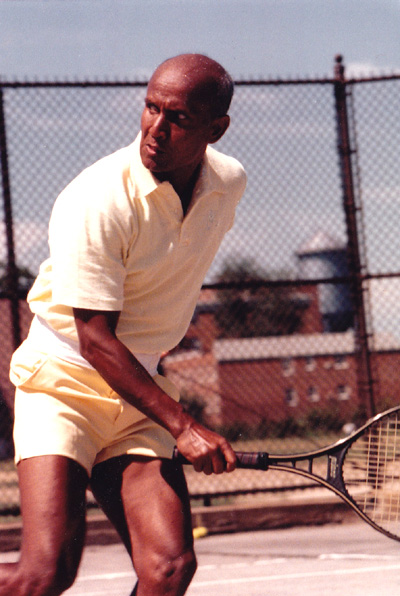

Over the next few months, Sri Chinmoy continued to practise daily, cultivating the body movements and strength necessary for a sound game. At the end of October, he attended the Colgate-Borinquen Tennis Classic in Puerto Rico. At this stage, he considered his main weaknesses to be his serve (which lacked the full wind-up that is essential for power) and his backhand (which was not of equal strength with his forehand). By concentrating on these two strokes in particular, he was able to formulate a potent serve and an effective, one-handed backhand.

Sri Chinmoy demonstrates his improved backhand. Photo by Dhananjaya

At this time, Sri Chinmoy also began to experiment with different kinds of equipment, such as shoes and racquets. He played with racquets that were strung as low as 25–30 pounds, and others that went up to 115 pounds and required holes to be drilled in order to fit a special nylon cord. Finally, he settled for a 72-pound racquet tension. Further modifications to the racquet itself included a one-inch extension to the grip. This was, in fact, prior to the time when such extended racquets became available commercially. He also tried various grip sizes and, after ranging up to five inches, now prefers a 4¼ to a 4⅜ inch grip in which the bracket is shaved down slightly so that it is actually somewhat smaller. On the whole, Sri Chinmoy selects large-face racquets and his most recent favourites have been the Prince Pro2 and the Wilson Cobra.

Sri Chinmoy’s tennis training intensified in December 1977 and January 1978 while he was on a three-week trip to Bermuda with many of his students. There he played countless games daily, as well as more formal matches with several professionals on the island and the president of the Bermuda Tennis Association. Later during the month of January, while on a trip to Puerto Rico, Sri Chinmoy played with tennis pro Jaime Gonzalez. On his return to New York, he took some private coaching from Ronnie Rebhuhn, head pro of the Great Neck Tennis Club on Long Island.

In his regular matches, Sri Chinmoy favours the Simplified Scoring System adopted by the World Team Tennis Organisation in 1974. Under this system, individual games are won by the first player to score 4 points. This eliminates the entire process of deuce and advantage which many people hold to be an archaic constraint on the game. Certainly, the simplified scoring system brings about a faster revolution of games. There are fewer chances for a player to recover from a losing position and long, drawn-out matches are replaced by clear and decisive victories.

For Sri Chinmoy, the sheer joy of tennis is never marred by a rigid adherence to the rules and regulations. Often, in order to prolong a fine rally, he will accept a ball that is obviously going to land beyond the baseline. Again, instead of putting a ball away with a passing shot to win a point, he may place it in a more accessible position for his opponent, thus keeping it in play a little longer. His whole game is permeated by a spiritual consciousness that is not attached to winning or losing. To opponents and onlookers alike, it is evident that Sri Chinmoy’s profound love of the game itself gives him a unique detachment from the results of his efforts. This spiritual poise, which is the hallmark of all his undertakings in the realms of athletics and the arts, imparts to his game a rare quality of repose. Losing crucial points does not disturb this inner balance, for he approaches each game with a sense of a new beginning, a new opportunity. Players are surprised to find him complimenting their good shots at critical moments or expressing an obvious delight in an especially swift exchange.

Sri Chinmoy’s love of tennis has also inspired him to stage a number of marathon tennis performances. In June 1978, for example, to celebrate the first anniversary of his taking up the game, he played 453 straight games against 89 disciple players, both male and female. The marathon series began shortly before 6:00 a.m. on June 13th and moved indoors at dusk. It finally came to an end at 11:10 p.m., approximately 17 hours later. The following year, for his second anniversary, Sri Chinmoy played 100 different opponents over three days, winning every game.

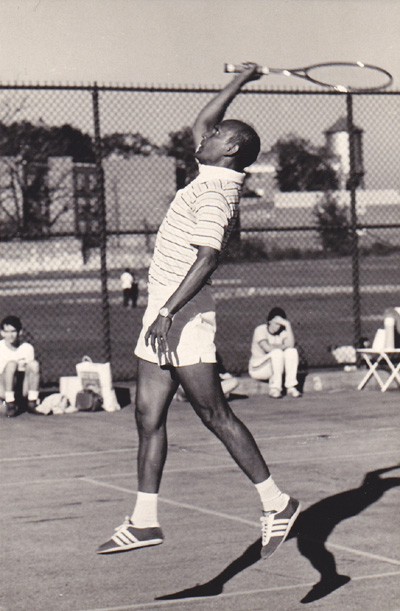

Sri Chinmoy leaps high to execute an overhead smash. Photo by Dhananjaya

This kind of event is nothing other than a celebration – a celebration not only of tennis, but also of ‘play’ in its purest form. The players delight in the game and they share their delight with those who are observing it. Ball boys, umpires, scorers, spectators – all are caught up in the thrill of moment-to-moment shots.

Because tennis invites participation in this way, it differs greatly from running, a sport which Sri Chinmoy began to practise seriously once more towards the end of 1978. Though previously a sprinter, he now tackled the longer distances, up to as far as 47 miles. Here, too, the emphasis was on stamina and endurance, the same qualities that he needed for his endless hours on the court. Running and tennis were to prove mutually beneficial, at least in the beginning. Running increased his on-court speed, while tennis gave him a proportionate abdominal and upper body strength that many distance runners lack.

Sri Chinmoy’s tennis game was clearly on the ‘upswing’! Discussions, such as the one held with Jack Kramer3 in California on September 30th, 1978, also helped to clarify certain points about the game. Their conversation probed the finer details of serve, spin, slice and net play:

Sri Chinmoy: Will you please advise me about the serve? Is it absolutely necessary to use the American twist?

Jack Kramer: Only if you want to have complete safety and keep people back by hitting deep. A serve is only as good as its depth and accuracy…

Sri Chinmoy: What about underspin and overspin?

Jack Kramer: Underspin is great for balls that are very short, because you can’t hit them hard and keep them in. It is also good for balls that come hard and deep. If a ball comes hard and deep and you don’t have time to hit a backhand drive, you can use your slice. It’s your defence.

In June 1979, Sri Chinmoy had another illumining meeting with a tennis legend. This time it was with Pancho Segura.4 The meeting took place in California and Segura advised him to work on his backhand.

On November 18th, 1979 in Queens, Sri Chinmoy played 102 single-set games, of which he won 82 and on November 22nd he played 140 games, winning an outstanding 106. This was only the beginning of an extraordinary series of weeks filled with tennis. During a three-week vacation in Hawaii, on the hot and unshaded courts of the University of Hawaii, he played a grand total of 1,398 singles games, in which he chalked up 1,023 victories.

Hard is it to fathom such a feat: that one man alone could play for so long against players who rotated and were, therefore, much fresher; that he could maintain his enthusiasm, energy and consistency. Truth to tell, it was his opponents who left the court looking ragged and spent, while Sri Chinmoy pressed on to yet another game.

In some respects, it may be said that Sri Chinmoy has tailored his game to meet the demands of such tournaments, where endurance is a major factor and the ages of most of his opponents are much less than his own. He replaces excessive running with excellent strategy, striking the ball at different angles, chopping it or causing it to sail high over his opponent’s head for a baseline lob. This kind of tactical game is only possible for someone who can accurately place the ball. Hence, it is not surprising that Sri Chinmoy believes placement is the single greatest determining factor. His view supports that of Australian tennis great Ken Rosewall,5 who has written:

“In tennis, it is not important simply to hit a fast ball, or to hit it a long way. This is a game where the most important thing is placement of the ball.”

When Sri Chinmoy is on the attack, his game is characterised by placement rather than by power, for power alone, he feels, is not sufficient to win points. Unlike many modern players, he is not content to play a waiting game of indefinite rallying until his opponent commits a fault; nor does he play a slam-bang game of baseline shots. What he prefers is a game of strategy – of disguised shots, drives with underspin and slice, lightning half volleys and shots like the lob, which can be transformed from a defensive manoeuvre into an offensive one by an experienced player.

At full stretch for a half volley. Photo by Dhananjaya

Troubled with persistent pain in his lower back, Sri Chinmoy cannot always hit the ball parallel to the ground. He counteracts this disadvantage by placing his racquet firmly down for low balls and catching them immediately after the bounce on the half volley. Like American Tom Okker,6 he has made this one of his best shots, swift and penetrating. Rosewall, who was also a master of the half volley, writes of this shot:

“The half volley is a real fighting shot and should be perfected.”

Sri Chinmoy’s ability to anticipate the play makes it extremely difficult to get shots past him, particularly when he is at the net. Seldom is he caught off balance or forced to cramp his stroke. His footwork is noiseless and sure. We do not find him sacrificing control or rhythmical co-ordination for speed, or losing points through an over-eagerness to crush the ball. He has learnt to take full advantage of his extensive repertoire of shots and to play with both skill and insight.

“The half volley is a real fighting shot.” – Ken Rosewall Photo by Dhananjaya

In 1980 Sri Chinmoy’s game gained new impetus when he was able to bring his weight down to 127 pounds. With his 5’7½” stature, his appearance on the court was now that of a much younger man. In both his running and tennis, this weight loss led to a significant increase in speed.

On April 19th, for four consecutive hours, Sri Chinmoy played four professionals at Randall’s Island, New York, winning 48 out of the 101 games played. Over the next few months, Sri Chinmoy Tennis Tournaments were held in Chicago, New York and Puerto Rico. These arose out of his direct encouragement of aspiring young players.

Observing his third tennis anniversary at the end of June 1980, Sri Chinmoy played 325 games with 77 different players. Of these, he won 284 games (over 87%). At the close of the year, in Tobago, he played a total of 266 games on seven different days, losing only 50. In each instance he played alone against a doubles team. His standard had now progressed to a different level.

It is August 1981. Each morning, after competing in a series of track and road races conducted in honour of his forthcoming 50th birthday, Sri Chinmoy arrives for tennis practice. His court is a makeshift area laid out on the handball court of Jamaica High School. The concrete surface is uneven, it is bounded on one side by a solid wall and it is open to wind. Yet it is here, in these modest conditions, that a superb tennis player has been nourished and this inauspicious ‘centre court’ has been the scene of some of the most enthralling tennis imaginable.

He has taken on player after player with unflagging energy and zeal and, over the space of four years, he has come to surpass all of them. Beyond the limelight of the pro circuit, Sri Chinmoy has been exploring the beauty and delight of the game in its purest form. Now, perhaps, the time is ripe for a new step forward. Of late, he has begun conceding three points in advance to his opponents and then attempting to struggle back and win the 4-point game against all odds. He has continued to challenge the best doubles teams single-handedly, playing with alleys on one side of the court and not on the other. This has forced him to cultivate even greater accuracy with regard to the placement of shots. In a single day’s play in July 1981, Sri Chinmoy won 23 out of 24 games played in this fashion, easily accommodating himself to the additional demands of this two-pronged attack. Recently, as many as four players have taken the net against him simultaneously and still he has maintained his winning edge. On Saturday, August 15th, for example, eight games were played with this unique formation and the final score stood at eight wins for Sri Chinmoy and zero for the opposing team. Even given that they may have toned down their regular game in order to give their spiritual teacher a sporting chance, it is still a remarkable achievement.

These recent innovations attempt to reproduce the uncertain and unpredictable nature of a real tournament situation. In spite of being placed under the handicap of squaring off against four players at once, Sri Chinmoy has proved his mettle. As in all his other activities, he has pushed tennis to the very limits. It is his relentless quest for perfection that compels him to keep transcending his own capacities. And tennis has provided him with the perfect metaphor for surrender to the divine. The tiny ball has no will of its own; it simply obeys the player unconditionally. As he writes in one song:7

I play tennis every day

To join my Lord’s Vision-Play.

I am the surrender-ball:

All joy in a body small.

Tennis, tennis, tennis game,

My heart’s perfection-flame.

Four fleeting years have seen Sri Chinmoy advance from a novice to a player of rare excellence. The next few years may hold even more startling improvements. Whatever the outcome of these future matches, Sri Chinmoy’s tennis will always be treasured by seekers because it reveals the calm repose, the spirit of play and the quenchless thirst for perfection of a lover of spirituality.

– Continued –

Copyright © 1981, Vidagdha Bennett. All rights reserved under Creative Commons license.

Endnotes:

1 This article was written in August 1981 when Sri Chinmoy was still a relative newcomer to the sport.

2 The history of the tennis racquet: About.com: Tennis

3 For more background on Jack Kramer see: Hall of Famers

4 For more background on Pancho Segura see: Wikipedia

5 For more background on Ken Rosewall see: Wikipedia

6 For more background on Tom Okker see: Wikipedia

7 The musical notation for this song is at: Sri Chinmoy Songs