Compiled by Vidagdha Bennett

The following incidents were narrated by Sri Chinmoy at different times.

|

|

|

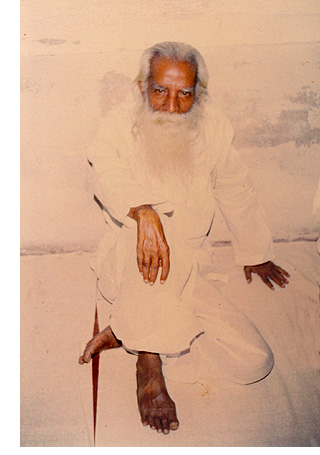

Sri Chinmoy took this photo of his first Bengali teacher, Prabhakar Mukherji, in the summer of 1972,

when he returned to Pondicherry for a short visit. |

|

1. My first Bengali teacher was my greatest admirer. His name was Prabhakar. He taught me Bengali and Sanskrit. I was not even six months in his class when he wrote an article about me! It was 26 pages long. This happened in 1944, the year I joined the Ashram. I was just a little kid and he had to write an article about me, saying what he saw in me and so on. Can you imagine!

Then he invited all the students to come to his place and listen to him reading the article. He offered them some milk and fruit and so forth, so they went. Such was his love for me.

2. I have always been a great admirer of Shivaji. At the Sri Aurobindo Ashram where I grew up, our teachers used to give us marks out of four. If you got four out of four, it was excellent; if you got three, it was very good; two was good; one was fair and zero was ‘tolerable’.

One time my Bengali teacher asked us all to write an essay on Shivaji. We had to write it in the classroom, not as homework. I was at that time around thirteen or fourteen years old. The teacher was so pleased with my essay that he gave me eight out of four! The principal came to know of it and he said to this particular teacher, “Are you crazy? How can you give eight out of four?” Then they had a serious altercation.

By giving me eight out of four for my essay on Shivaji, my Bengali teacher – who was so fond of me – got into trouble with the principal!1

3. Whenever I finished some poems, I used to literally run to my Bengali teacher, no matter how busy he happened to be. I was so anxious to get a little word of appreciation from him. I would come with three or four poems and he used to appreciate them with utmost sincerity. So many things he used to see and feel in my poems. Never, never did he discourage me.

There are many poets who give up because they are unbearably criticised. They are cursed because of undivine criticism. But my Bengali teacher was always so kind to me.

4. My Bengali teacher was so fond of me. One funny incident I remember. He liked to smoke, but he did not smoke in front of us. He used to smoke at home late at night. Once I was passing by his house. It was ten o’clock at night. I saw him outside in the street smoking. As soon as he saw me, he did not extinguish his cigarette, he just put it inside his pocket! Then he started talking rubbish, pretending that nothing was wrong. He was positive that I did not know about the cigarette.

I had begged him so many times to stop smoking. So when I caught him, I said to myself, “Let your pocket burn!”

We chatted for a few minutes and then, as I was leaving, I said to my poor teacher, “By the way, I know the condition of your pocket!”

5. In 1955, when I published my first book of poetry in the Ashram, I asked him to write the Introduction. The book is called Flame-Waves and it came out on my 24th birthday. This is what he wrote:

INTRODUCTION

To introduce a poet to the public is sometimes almost as tempting as to be oneself a bard; especially when the author is a close relation of the introducer and when the former is more gifted than the latter.

Just eleven years ago, one day as I was busy with my students in the Bengali class in our Ashram School, a boy of thirteen was brought to me. I found myself looking for the first time into Chinmoy’s intelligent but innocent and simple face. In a couple of years he joined my Sanskrit class, after having been initiated into that language by his eldest brother Hriday Ranjan, who is a devoted student of the Rig Veda and a lover of poetry.

Within a few days, Chinmoy brought me some Bengali poems of his, not in a spirit of display but for correction. I took his manuscript and without his knowledge showed it to the Secretary of our Ashram, Nolini Kanta Gupta, who is a celebrated savant and a front-rank writer. It was returned with the comment, “The boy has merit; encourage him, he will produce even better poetry in the future.” The present book has also been seen in manuscript.

In 1946, the poet rendered Sri Aurobindo’s story ‘Kshamar Adarsha’ (Ideal of Forgiveness) into Bengali verses – no less than two hundred lines. Poet Nirod Baran took it to our Master who remarked: “It is a fine piece of poetry. He has capacity. Tell him to continue.” The poem was published in a journal in March 1948, with an appreciative Editorial note.

Somewhere in 1950, while one evening I was all alone, absorbed, in my room, Chinmoy suddenly knocked at my silence, and soon a heap of typed sheets was before my eyes. They were all ‘Prayers’ in English, composed in prose but with a fragrance of genuine poetry.

Since 1953, he has been contributing now and again to ‘Mother India’. I thank its Editor K.D. Sethna, a prominent poet of modern India in English as well as an erudite exponent of Sri Aurobindo-Literature, for his encouragement and advice to the young poet in various ways.

Romen, the author of ‘The Golden Apocalypse’, also deserves my thanks for giving Chinmoy a push on the path of English poetry.

Lastly, a word of thanks to Chinmoy himself for choosing me to write this Introduction. He is too unassuming to ask for appreciation, but when some one suggested my name, he exclaimed, “Oh! I got inspiration from him in my younger days, that continues even now. And who else will appreciate me so affectionately?”

Though perhaps out of place here, yet it is interesting to note that Chinmoy got the Blessings of our Mother and Sri Aurobindo as early as 1933, when he came here for the first time as a child of a little above twelve months! May he continue to receive their Grace!

‘Flame-Waves’ is the maiden work of the author, dedicated to our Mother Divine as a humble offering on his own birthday, on the 27th of August, 1955. The title, of course, indicates the Aspiration in the inner being of the poet, at once flowing and fiery, wide-spreading and upward-leaping.

Prabhakar Mukherji

Sri Aurobindo International University Centre,

Pondicherry,

27-8-1955

6. Chinmoy’s brother Chitta was extremely proud of his younger brother’s literary endowments and especially grateful to Prabhakar Mukherji for encouraging him. In his notebooks, Chitta writes:

“Right from his childhood, Madal had a tremendous desire to write books and print books. I am so grateful to God that He has fulfilled my youngest brother’s desire. In 1955, when Madal’s first book in English,“Flame-Waves”, was published, his Bengali teacher, Prabhakar Mukherjee, who was all affection and love for Chinmoy because he was by far the best student in his Bengali class, in his introduction wrote:

‘In 1946 the poet [Chinmoy] rendered Sri Aurobindo’s Bengali story, Kshamar Adarsha, ‘The Ideal of Forgiveness’, into Bengali verse – no less than 200 lines. The poet Nirodbaran took it to our Master, who remarked: “It is a fine piece of poetry. He has capacity. Tell him to continue.” ’ [That was Sri Aurobindo’s remark.]

The poem was published in a journal, Partha Sarathi, in March 1948 with an appreciative editorial note. He had written this poem when he was 14 years old. At such a tender age, he showed his great talent. No wonder he has become a celebrated poet! We noticed all along in Chinmoy the influence of Tagore, Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo. When Chinmoy was in his teens, we saw in Chinmoy – Tagore, the manifold capacity; Vivekananda, the indomitable hero; and Sri Aurobindo, the founder of Integral Yoga.” 2

– End –

Endnotes:

1 Sri Chinmoy, Shivaji, Agni Press,1997.

2 Sri Chinmoy, My Brother Chitta, Agni Press,1998.