The Flute Discovery

In 1976, Sri Chinmoy made two momentous musical discoveries: the esraj and the flute. The esraj he came across in February, in a book of Indian instruments. When he obtained one shortly afterwards, the haunting effect of this bowed instrument delighted his musical ear, and the esraj subsequently accompanied him on a visit to Australia at the end of February.

It was to be here, in Australia, that Sri Chinmoy would become acquainted with the classical Western flute. Previously, he had played considerably on the simple Indian reed flute. Although this instrument has a tremendous purity of tone, he found it lacking in the agility needed to convey subtle nuances and shades of expression. Now, one of Sri Chinmoy’s disciples, a young girl of nineteen years, introduced him to the modern transverse flute. The grace of the instrument and its clear, limpid sound appealed deeply to Sri Chinmoy and, on March 10th, he requested the opportunity to play it.

The occasion was a bus trip to Healesville Animal Sanctuary just outside Melbourne. As the bus rolled through the foothills of the Dandenong Range, Sri Chinmoy’s first lesson began. His young disciple carefully explained the art of embouchure and fingering and, in less than two hours, when the bus had reached its destination, Sri Chinmoy had mastered the basic scale. Alighting from the bus, he delighted everyone by walking through the various bird and animal compounds playing the flute to entranced kangaroos, cockatoos and all who would listen.

He was the student and his disciple was the teacher. It was an unusual reversal of roles. But how long can such a one disguise his true nature? How long to hide with utmost humility in the role of a novice musician? The great musical wealth housed inside his breast could scarcely be contained.

A Master Musician

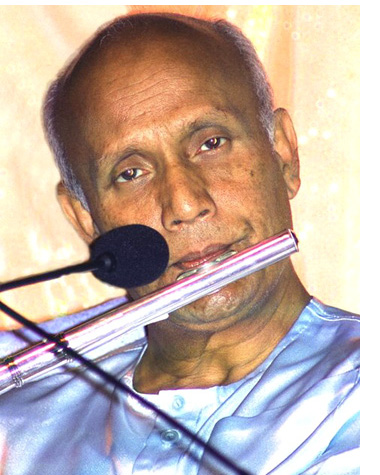

What can be said of Sri Chinmoy’s progress on the flute? Technically, the advances that he made over the next few months were extremely rapid and significant. His flute became his constant companion. Whether reclining on his couch, travelling in the car or even walking along some solitary corridor, the silver tip of the upraised flute could be seen, with gentle fingers dancing over its surface, scattering notes of radiant beauty.

It seemed that long in advance of fully mastering the flute technique Sri Chinmoy could hear the ethereal tunes he would ultimately produce. He sought a note of pristine purity, a peace-breathing, soul-stirring note. This led him to experiment with the entire flute range – from bass and alto flutes through to C soprano and piccolo. He played flutes that were silver, gold and platinum-plated, inexpensive student models and hand-made masterpieces. His most frequent choice was a Haines C soprano flute in the Boehm style, with closed holes. Its clear, limpid tone was capable of every conceivable nuance.

As Sri Chinmoy continued to practise more and more, he found that technique, as such, no longer stood in the way of translating his inner songs into musical form. Deploying all the acoustic properties of the flute, he was able to play with infinite variation and expressiveness. The notes that he created were clean, crisp and finely articulated; he had a thorough appreciation of phrasing; he was especially adept at producing incomparable sequences of notes – slurs, trills, unusual intervals and turns. He was able to make single, detached notes last endlessly by virtue of his excellent respiratory control.

In November 1979, Sri Chinmoy added a new and surprising effect. The flute was made electric and connected to an echo chamber. This had the result of amplifying and prolonging each individual note so that the listener gained the impression of a continuous overlay of sound. In effect, Sri Chinmoy had added the mountain summit or the farthest horizon to his playing. It was the note heard from afar, floating across the valleys with bird-like clarity, borne on the wind to pierce our hearts.

The Silver Sound

The pure, melodic line that constitutes the essence of Sri Chinmoy’s music sets it apart from the Western system of harmonics. The evolution of Western music is based on the belief that consonance of sound is most pleasing to the ear. This has led to the rich orchestral effects of Western classical music. Sri Chinmoy, however, inclines towards the delicate structure of Eastern classical music, with its emphasis on simplicity and clarity. He has ever preferred the distinct melodic thread of the single instrument, uttering its song alone and unqualified. The sound issues from the silence gradually; it does not break or disturb it. And it returns to this silence-source at the close of the song – like a small wave spinning out the length of the shore and then sinking back into the ocean depths.

Explaining his views, Sri Chinmoy writes:

“I personally feel that there are many, many songs which will be better if you do not embellish them with harmony. If you carry just the melody, they will be really haunting. Then the pristine purity of the song will remain. Our haunting Indian melodies go right to the very depth of the heart and soul.”

When Sri Chinmoy plays upon the flute or the esraj, unaccompanied by other instruments, the musical instrument becomes his own voice, full of luminosity and power. This music is of a kind that cannot be poured into tight and traditional forms. It recognises no boundaries, save those accents of feeling which the flautist seeks to render. It presupposes only the awakened heart of the aspiring seeker, whose ear is the deputy of his innermost being.

What is it that makes hearing Sri Chinmoy play his flute such an extraordinary experience? One might be seated in a large meditation hall, rapt in silence, when from the stairwell a trill of wondrous notes, like some invisible perfume, touches the delicate fibres of the soul. Helpless before such magic, the soul inhales them deeply and melts in them. A glissando, a sudden cascade of notes, and the air is subsumed once more by silence.

Immersed in the Divine

Sri Chinmoy relaxes in his chair, his eyes closed in sublime peace, his plaintive flute shedding soft, low notes. There is something in the quality of his playing and in the outline of his figure in repose which strikes an ancient chord.

The image of the divine flautist is one of the most beautiful flowers of Eastern mysticism. Sri Krishna played upon his flute in the forest of Brindaban. Hearing his call, the cowgirls living at the edge of the forest would leave their homes to join him in his divine play.

The experience of seeing and hearing Sri Chinmoy play the flute summons similar associations. Gone are the leafy forest trails and lotus-filled ponds, gone the peacocks and placid, white cows, yet the same serene smile dances across his countenance and his flute music evokes the same inner thrill. In Sri Chinmoy, we discover anew someone who seeks to awaken aspiring humanity and lead it into the presence of the Divine. He frames songs of human transformation to release mankind from the slumber of inconscience.

In poem after poem, Sri Chinmoy pays homage to Lord Krishna through his portrayal of a mysterious and evanescent flute-player. None can ignore the peremptory summons of his flute:

There goes my Beloved, my sweet Lord,

The anklets ringing on His Feet.

I hear the music of His Flute

Vibrating through the horizons.

If ever my cowherd boy should cast a glance

Behind Him, still He only goes forward.

Let my eyes follow the track my

Beloved treads.

In the twilight hour of the day, with a sweet

And serene smile,

Leading the herds of varied light,

My cowherd boy goes.

Lord Krishna, the eternal youth, draws his devotee through the siren-like music of his flute. Listening to Sri Chinmoy’s flute, it is possible to feel the same unfathomable call of the Divine. It may be that in each and every age the hearts of seekers will be captivated by a gentle flautist who, taking up his instrument, diffuses a spontaneous flow of notes such as none has ever heard before, nor will hear again.

Sri Chinmoy in Concert

April 7th, 1982. Sri Chinmoy has come to Carnegie Hall, showplace of the world’s premier musicians, to make his unique offering – a free musical concert in which he will perform on esraj, flute and harmonium.

The vast stage discloses the familiar, meditative figure of the master. He is seated in an upright chair. Slowly he bends down and picks up the flute by his side, feeling the shape he knows so well. He lifts the silver mouthpiece to his lips and releases the first long, fluttering note. As all the air begins to vibrate with his musical creation, we seem to discover some long-forgotten concord, some melody whose absence has made our hearts heavy with the ache of centuries.

Some audience members, finding themselves swept away by the magic of the music, impute to it heavenly scenes and vistas. In a 1980 review in the Washington Post, Richard Harrington was moved to write:

“Sri Chinmoy performed a lovely, very modern flute essay, pretty enough to make a deer lay its head on the musician’s lap.” [June 7th, 1980]

The pastoral arcadia to which this critic was transported vividly reminds us of Stendhal’s statement: “The only reality in music is the state of mind it induces in the listener.”

On June 4th, 1982, Sri Chinmoy performed before an audience of 2,400 at the Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall in San Francisco. After the concert, one admirer wrote:

“Sri Chinmoy’s concert was Heaven! Thank you for a beautiful experience. His presence of love itself was worth the trip to the city. Then, as he became the perfect instrument through which the music of the universe could express itself, I was absolutely transformed.”

The experience of Sri Chinmoy’s flute music is subtle but unforgettable. We, who are present at its blossoming, have but a partial glimpse of its immense and ultimate role. Already seekers far and wide are conscious of the presence of a higher, nobler and purer inspiration in the world. And perhaps, like the deer that the Washington Post critic envisioned, we may eventually follow this flute trail to the Lap of the Supreme.

– End –

Editor's note: The author originally wrote this article in 1982.

Listen to Sri Chinmoy Flute Music

- More Flute Music by Sri Chinmoy at Radio Sri Chinmoy

Copyright © 2009, Vidagdha Bennett.

All rights reserved under Creative Commons license.