by Dr. Vidagdha Bennett

May, 1984

Three years have elapsed since the first part of this article appeared. If one were to graph Sri Chinmoy’s progress in tennis during this time, it would show a steady escalation, which was particularly intensified during the warmer months from April to September.

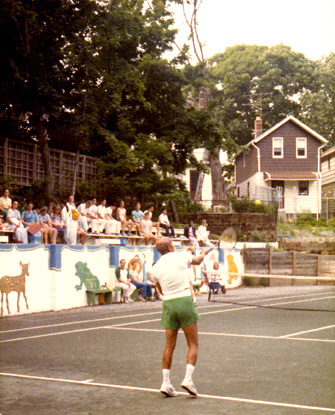

As conditions at the Jamaica High School handball area deteriorated, Sri Chinmoy expressed a wish to have a permanent tennis court of his own. He was able to purchase a narrow and oddly shaped plot of unused land in the neighbourhood and his students constructed a clay court on the site. It was a snug fit, to say the least. A doubles court is normally 36’ x 78’ with a 12’ perimeter on each side and a 21’ perimeter behind the two baselines to create extra playing area. Sri Chinmoy’s court had less than half these perimeters. At his home end, a small blue hut was built where he could rest between sets. To one side was a high, solid wall that supported bleachers for spectator seating. On the other side was a wire fence with windproof netting. The far end had its own set of unusual obstacles – a set of steps, a low wall and a gate which seemed to be in constant use. The court was finished on June 9th, 1981 – just in time for Sri Chinmoy’s fourth tennis anniversary.

Sri Chinmoy serving from his home end. This was before his blue hut had been built in the area where his chair and drinks can be seen. Photo by Vidagdha, circa June 1981

Sri Chinmoy serving from his home end. The photo clearly shows the proximity to the players of the stone wall. Photo by Vidagdha

Sri Chinmoy returning a shot from Ashrita to his forehand side. The narrow perimeter on this side is clearly evident. In time, wisteria has grown to cover most of the fence. Photo by Vidagdha

Over the years, this modest tennis court has become a place of pilgrimage for seekers. It is used by Sri Chinmoy and his disciples for meditations, singing, dramatic performances and many other spiritual activities. Within its precincts, conversation is at a minimum. One becomes filled with the holiness and sanctity of the place. And yet, it began as a humble tennis court.

During the warmer months, Sri Chinmoy developed a routine whereby he would arrive at the court between 7:15 and 7:30 a.m., often after an early morning run, perform a set of ten or twelve weightlifting exercises, and then work through a range of practice shots on the court. Only then would he commence serious play. Mostly, his partners were local disciples. Each one would play two games with him and then another player would take over. Very few were able to take any points from him.

In 1981, however, Sri Chinmoy’s game received new impetus when he discovered a worthy rival in the person of one of his Californian disciples. Mahiyan (John Savage) was a former circuit player. He had played in the French Open and he was the practice partner of Pat Du Pré,1 at that time ranked 12th in the world. Initially, when Sri Chinmoy played Mahiyan, he was outclassed by the sheer brilliance of Mahiyan’s game, particularly his consistent and relentless ground strokes. Enjoying this new challenge, Sri Chinmoy set aside his habitual routine of playing only two games with any one partner at a time. His matches with Mahiyan grew into lengthy battles of attrition that did not cease until both sides were ready to drop with fatigue. And Sri Chinmoy thrived on such encounters, awaiting them with eager anticipation. His matches with Mahiyan acted like a catalyst, suddenly compelling him to reach a much higher standard of play.

As the months went by, he gradually developed answers for Mahiyan’s best shots and was able to play offensively, not solely defensively. He drove Mahiyan from corner to corner, until the younger man was dripping with perspiration. A major breakthrough came when he was able to return Mahiyan’s big serves on a regular basis. Although forced to play them from a point 2-3 metres behind the baseline, Sri Chinmoy’s return of service became a potent weapon.

His improved game was put to the test on April 16th, 1982 when famous tennis coach Alex Mayer,2 a former world’s number 7, paid him a visit. As the two players began to rally, Mayer automatically slipped into his role of coach and adviser, feeding the balls to Sri Chinmoy at varying angles and depths. After thirty minutes, Sri Chinmoy invited Mayer to play a match and so began a game that was quite unlike any other, a game full of gentlemanly consideration and of master shots that held the spectators spellbound with admiration. Both players dug deep into their reserve of shots, displaying utmost finesse and skill. “I thought this life was going to be easy. Nobody promised us an easy life,” joked Mayer between sets.

The final scores after one hour of play stood in Mayer’s favour: 6-2, 6-1, 6-1. However, he refused to accept the result as it appeared on paper, for it was his unshakable conviction that Sri Chinmoy had allowed him to win. “You are so great, you make other people great,” he told his host, putting his arm around Sri Chinmoy’s shoulders.

During the months of May, June and July 1982, Sri Chinmoy consolidated his game even further. At the same time, he plunged deeply into running. The choice between the two sports was often difficult, as they were no longer proving mutually beneficial. Early in July, he commented, “Tennis and running don’t go together. If I don’t play, then I will really make improvement in my running. But tennis gives me joy. Running does not give me that kind of joy.”

Sri Chinmoy playing at an outside venue.

Sri Chinmoy’s love of tennis was exemplified on July 4th. For some weeks, he had been ill, but on this Independence Day weekend he ventured upstate to open an old-time country music festival. Afterwards, he gathered with his students at a nearby clay court. He entrenched himself at one end just after midday, under a scorching sun. His opponents rotated in two’s and four’s. Sri Chinmoy’s mood was quiet and he interrupted the flow of games at regular intervals to conduct special on-court meditations. His students would clamber down from the grassy slopes where they had been watching the games and sit on the court to meditate with their teacher.

By late afternoon, the players’ footprints, like so many tiny bird tracks, trailed across the entire surface of the court. Sri Chinmoy called a final meditation at 5:30 p.m. The energy that he had poured into the game throughout the afternoon was now turned inwards.

Back in New York, he began to prepare for the arrival of Mahiyan from California and Anugata (Bach) from Chicago in August. During this time, Databir (Watters) worked closely with him, peppering his shots to Sri Chinmoy’s weaker areas.

Although Sri Chinmoy was suffering considerably from back pain – the result of a fall on the ice some years earlier – he settled into a routine of two hours’ practice each morning and each afternoon. These hot, summer days were distinguished by some classic matches. On July 14th, to cite a typical day, Sri Chinmoy arrived at the court for his second session at 5:00 p.m. His opponents were to be Databir and Ashrita (Furman) in tandem. Enjoying himself in an informal way, Sri Chinmoy sent balls rocketing to all corners of the court. Soon the two boys were covered with clay streaks. Like baseball players sliding in to base, they skidded to the net and then a swift return would cause them to jerk sideways or backwards. Sri Chinmoy gave no indication of easing the pressure. At one point, after nearly two hours of play, Databir fell to his knees and prayed out loud that Sri Chinmoy’s ball would not clear the net. His antics drew much laughter. Later, while chasing a ball, he ran headlong into the side wall and stayed flattened against it, desperately tired. After the match was over, the two boys as well as the umpire and ball boys all gathered round Sri Chinmoy and, like comrades, they discussed the different strokes of the top professional players.

The following day at 6:00 p.m. the same pattern was repeated, this time with the addition of a few more players. Sri Chinmoy arrived directly from a long run. Before playing, he put on two supportive belts for his back. In addition, he conceded two points in advance to each doubles pair. It seemed as though they had every advantage over him.

As Sri Chinmoy began his first game, his eyes sparkled with the joy of this innocent combat. Like Arjuna stringing his famous bow Gandhiva, he sent shots whizzing across the net. He darted in to meet short returns with his famous half skip and, when he missed a shot, he pivoted on one foot – a signature move like a dance step.

At 7:30 p.m. people began arriving for meditation. Instead, they found themselves witness to a remarkable display of energy and skill. In the final moments of play, Sri Chinmoy employed his whole repertoire of dipping and angled shots, spins and lobs, to defeat the opposing team. The scores stood at 50-35 games in his favour. Smiling, he said: “Almost nearing 100 games – so one can become tired!” He sat in his chair for the first time in over three hours and his students sat before him in rows on the court. He placed one finger over his lips as he meditated, like the spiritual masters of yore who, speaking in sign language, conveyed to their disciples the message of silence. The soft night lapped at the edges of our paradise and we knew that this precious moment belonged to eternity.

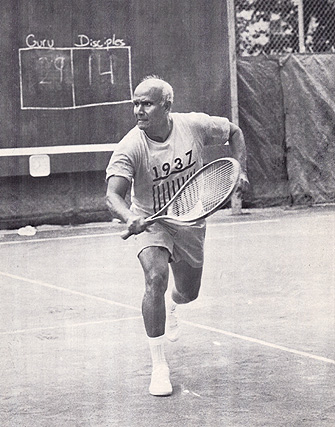

Towards the middle of July, Sri Chinmoy began to intersperse his tennis with poetry. On July 17th, he inaugurated the first in a series of chalk poems, which he wrote on the green scoreboard that was fixed to the wire fence. He asked his students to consider the tennis ground as their illumination-ground.

On July 27th, after concert tours to Rhode Island, North and South Carolina, Sri Chinmoy admitted that he was suffering from very poor health. In particular, he was troubled by constant fevers. However, he still continued to practise. On August 10th, his mighty nemesis Mahiyan arrived in New York and this gave him boundless joy. He immediately invited Mahiyan to play and so began an intense match that was to last over two hours. It was the kind of game Sri Chinmoy relished, with interminable rallies filled with long drives and crisp volleys. Each player employed his full artillery of shots.

Every day Sri Chinmoy took up his tennis appointment with Mahiyan. To the delight of all, he frequently spiced their arduous games with humorous comments. On one occasion, he exclaimed, “Now we are ready for Wimbledon!” At other times, he would warn Mahiyan in advance of a winning shot by calling out ‘bullet’ or ‘ace’ or ‘now you are gone!’ His praise of Mahiyan’s good shots was unstinting. Mahiyan’s grace on the court, his footwork, body positioning and flawless execution of shots compelled Sri Chinmoy’s admiration. His is the classic style of play, whereas Sri Chinmoy has adopted a more unconventional approach utilising greater wrist movement. This results in flicking shots that are extremely difficult to anticipate.

Playing set after set, Sri Chinmoy and Mahiyan established a momentum which both were reluctant to break, even if it meant playing to the point of exhaustion. One day, after a lengthy match which extended into dusk, Sri Chinmoy sank into his chair, while Mahiyan slumped to the ground on his side of the court.

“Oi, Mahiyan, how do you feel?” Sri Chinmoy asked, weakly.

“Terrible, Guru!” replied Mahiyan with feeling.

No one who watched their encounters in the last half of August 1982 will ever forget the thrill that came from seeing Sri Chinmoy perform at such a peak. We were transfixed with awe that he could maintain such a pace. One day, after first playing in the morning, the two combatants met again in the early evening, barely recovered from their previous rigours. These evening games were especially prolonged, frequently extending to more than thirty exchanges before the point was decided. Finally, Sri Chinmoy won the second set 7-5 and, in a spontaneous gesture of joy, he threw his racquet high into the air. It was something we had never seen him do before.

On some days, he requested Mahiyan and Anugata to face him as a pair. It was a fearsome combination, for Anugata had developed a professional service that was virtually unreturnable. It averaged between 95 and 110 mph and had tremendous kick spin, forcing Sri Chinmoy to play a high backhand return. On August 20th, these two players defeated Sri Chinmoy 6-2. Yet, by the very next day, he had analysed his weaknesses and was no longer vulnerable to the same degree. The result was that he defeated them 6-4. On August 23rd, a host of doubles teams lined up against Sri Chinmoy. The final score in his favour was 20-1.

Sri Chinmoy was in sparkling form at this time, responding to the pressure of game after game with superlative ground shots, delivered with pinpoint accuracy. He aimed his returns at his opponents’ feet, used cunning passing shots and lightning half volleys. In some matches, he delighted in edging up to 3-0 so that he could gamble on an attacking shot to take the match. At other times, he derived joy from fighting uphill in his game scores against overwhelming odds. His astute perception of the flaws in his opponents’ games and his unwavering concentration helped him to withstand the terrific pace and onslaught of a doubles team.

It was noticeable during these gruelling matches that he conserved energy in various ways. Unlike most players, who continually adjust their position with a succession of tiny sidesteps, his feet were planted firmly on the ground. He relied rather on his innate sprinting ability and a curious, utterly personal, skip – like an Indian classical dance step – which brought him to the correct position.

Sri Chinmoy is extremely light for a tennis player. At 5’ 7½” he is just ½” taller than the great Ken Rosewall and yet he averages 133 pounds, while Rosewall’s competitive weight was 140. Despite his slight build, Sri Chinmoy is able to inject remarkable strength into his shots. He is also adept at delicate, feathery shots and at overhead lobs which send his opponents scampering towards the baseline, flailing futilely with their racquets. He has brought his unique imagination to the game of tennis with surprising results.

The last days of August 1982 continued the tournament atmosphere that had been established. On August 24th, he lost to Mahiyan 4-6 and defeated Anugata 6-3. The following evening, he played 26 games, winning 15. Finally, on August 26th, the day before his 51st birthday, he played over three hours of intensive tennis with Mahiyan and Anugata. The results stood evenly deadlocked: 23-23. The standard of tennis in these matches was unquestionably brilliant. Sri Chinmoy had refined the half volley into a versatile weapon rather than an emergency tactic. Perhaps his reliance on this shot developed as a foil for Mahiyan’s towering presence at the net. Knowing Sri Chinmoy’s fondness for angled passing shots, Mahiyan often rammed his approach shots down the middle to land at Sri Chinmoy’s feet. Then Sri Chinmoy would use the half volley lob to scoop the ball up and send it over Mahiyan’s head or dribble it just over the net.

His next intensive bout of tennis came in late December 1982, when he visited Japan. Many of his matches were centred at a local court in Kyoto. Although the surface was uneven, it was extremely soft and Sri Chinmoy found that this eased the pressure on a very painful right achilles tendon injury that had developed through sprinting. The weather was brisk but clear and he soon began to find his form. The irregular bounce forced him to change his style of game and come to the net with an attacking volley. Under these conditions, his volley and overhead shot quickly improved. At this time, he was playing with a Weed racquet strung at 58-60 pounds with a nylon string.

On December 27th, Sri Chinmoy challenged Mahiyan to game after game. When the two players could barely see each other in the enveloping darkness, Mahiyan called out across the court, “Are you still there, Guru?”

“Yes, yes, I am here,” came the reply and they went on to finish their game. The final scores, in Sri Chinmoy’s favour, were: 6-4 7-5 3-6 5-7 1-6.

Sri Chinmoy arrived in Okinawa on December 28th. During his visit to the island, he played tennis on a basketball court, which his students had marked out. As usual, he blended the strict discipline of meditation with the game. Every fifteen minutes or so, he would cease playing and offer a brief meditation. Thus the court became the focal point of each day. At times, the game of tennis was forgotten altogether and the routine became a metaphor for the inner life of contemplation and the outer life of dynamic action.

Sri Chinmoy’s next spate of tennis was in April 1983, when his students gathered to celebrate his 19 years in the West. After the winter months of limited physical activity, Sri Chinmoy’s back was giving him trouble. Consequently, he concentrated on weights and flexibility exercises to regain his condition. On April 7th, he played Mahiyan for the first time since Japan and defeated him 5-0. Sri Chinmoy was so thrilled with this unexpected win that he offered all his students a special five-item prasad that evening and presented Mahiyan with a trophy and a huge cake, saying, “I get such joy when I play Mahiyan. He makes me forget my pain.”

On April 13th, the anniversary of his arrival in the West, Sri Chinmoy ran and walked 19 miles. By April 21st, the inclement weather had cleared slightly and he was able to return to the tennis court. In the late afternoon, he played Mahiyan, winning 6-4. The next day, they played again. This time Sri Chinmoy lost 4-7, and so Mahiyan offered him a trophy and a cake for losing. Sri Chinmoy said: “I am accepting this with infinite love from my heart and infinite gratitude from my soul. You come to New York and you give me such joy and I become a player. When you leave I touch rock bottom. No inspiration, no aspiration to play tennis.”

Sri Chinmoy then went on to talk about his game, making some interesting revelations: “Service I can’t do because of my back. Each time I serve hard, I become so tired that it is like playing two games.” Then, as an afterthought, he added: “My backhand needs topspin and my forehand ground strokes need to be more offensive.”

On April 23rd, Sri Chinmoy had a truly classic encounter with Mahiyan. The final score, in his favour, was: 6-4 6-3 10-8. This was Mahiyan’s departure day and Sri Chinmoy farewelled him with flowers and a special song. Finally, he placed a laurel wreath on Mahiyan’s head.

Over the next few days, Sri Chinmoy continued to play upwards of four hours a day. On April 29th, he played against various doubles pairs, winning 43-1. Then he took on four women players at once, defeating them 8-0. That same afternoon, he once again scored an impressive victory against the men’s doubles teams, winning 55-5. This brought his score for the day to 98-6. Just after 8:00 p.m., he called a meditation on the court itself. Afterwards, he moved to a particular place on his right-hand side and made a mark on the green clay. He asked the tennis court workers to keep the mark. Later he explained that during the meditation, he had a vision of a fountain of light shooting up from the ground at that point. The fountain was many-coloured and very beautiful to behold. From that time on, that particular place was preserved as sacred. A circle was drawn around it and it was covered at night. People took care never to tread inside the area, which was about one foot in diameter.

On May 1st, 1983 Sri Chinmoy ran ten miles of the Long Island Marathon. Around this time, he also began to introduce sprint training into his regimen. In every field, he was expanding, seeking to improve and reaffirming his commitment. The combination of tennis, running and weight work had made him inordinately strong. He once asked that his racquet be strung over 80 pounds, like Björn Borg, a former world’s number 1 from Sweden.3 Mahiyan, back in New York for Sri Chinmoy’s tennis anniversary on June 13th, said: “It will break your wrist, Guru.” “Do it,” was the answer.

Sri Chinmoy’s tennis anniversary had the atmosphere of a festival. During the day, he played with each of his students for three minutes and, in the evening, he played against Mahiyan. During one rally, there was a jaw-dropping 167 exchanges of the ball. In another game, Sri Chinmoy astonished everyone by resurrecting his soccer prowess and returning the ball with his head! Indeed, it seemed that to return the ball every time, against all odds, gave him far more satisfaction than actually winning. For what did it signify to make a point, except that the fun should end and have to start all over again? But how many people could play like this? Most players, as they become physically tired, grow mentally tired also. They begin to falter in their concentration and become less patient during rallies. Then, in order to reduce the amount of physical effort involved, they start to take risks. Mahiyan was unique in being able to maintain his standard for long periods of time and not suffer such lapses of concentration.

During the next few months, Sri Chinmoy gave up distance running entirely in order to devote himself to sprinting. The World Masters Games were scheduled for the end of September in Puerto Rico and he aimed to compete in several events. The effects of this sprint training on his tennis game were immediately apparent. He began to rush the net, a tactic he had rarely employed in the past, and he was able to cover the entire court with explosive speed.

From August 3rd to September 9th, he competed in fifty sprints and short distance races. On August 11th, to take a sample day, he ran a 50-meter race in 8 seconds, followed by a 60-meter race in 9.3 seconds. He then went on to score a 6-4 6-3 victory over Mahiyan at the court. Later the same day, during a heavy downpour, he defeated various other players 6-3 and was himself defeated by Mahiyan 9-11. Frequently, the speed at which he chased balls across the court would pitch him into the fence at the side boundary, but he was able to recover and be back on court in time to save a return.

On August 13th, Sri Chinmoy was due to play in the first round of the United Nations Tennis Tournament. It was four years since he had last played there. Now he was no longer a novice, but a seasoned player. From 8:00–8:20 a.m. Mahiyan gave him solid hitting practice. Later that morning, at the tournament, Sri Chinmoy lost by a very narrow margin to the top player in the tournament. The scores were 7-6 7-5 against him.

Upon returning to his own court at 11:30 a.m., Sri Chinmoy played a leisurely game with the Nepalese ambassador and his sons, defeating them in straight sets. He then suggested that Mahiyan come forward for an exhibition game. Suddenly, Sri Chinmoy’s whole approach was transformed. He pounced on low balls, hit others on the run and blasted his baseline shots. He won the match 6-1.

At 6:21 p.m. that same day, Sri Chinmoy took some instruction from Mahiyan on the serve and practised by serving 51 times. After that, he played various doubles pairs, winning 14-10. By this time, he had grown very tired and his right hand was numb from holding the racquet. Still, he challenged Mahiyan alone and won 6-3. It was the close of a long day.

On August 14th, Sri Chinmoy focused largely on sprinting. He recorded a time of 17.7 seconds for 100 meters, and then ran five 200-meter time trials, with a best time on the day of 38.7 seconds. At 8:20 a.m. he came to the tennis court and played two sets with Mahiyan. It was superlative tennis. Every point became a gripping duel. For a long time, Mahiyan was able to keep Sri Chinmoy on the baseline by smashing successive overheads. Sri Chinmoy was enjoying being on the receiving end of these thundering shots and testing his own ability to return them. In spite of the unrelenting barrage, he managed to outfox Mahiyan with his lobs and passing shots, winning the first set 6-4. Before moving on to the second set, he joked with Mahiyan: “You have meditated for such a long time. You will defeat me – you will see!” During this second set, the points see-sawed between the two players: Mahiyan’s long reach made him invincible at the net, while the absence of tactical errors on Sri Chinmoy’s part kept the pressure on Mahiyan. In the end, Sri Chinmoy won 6-2.

In the late afternoon, Sri Chinmoy practised his serve 100 times. He then defeated Mahiyan 6-4. Following this game, Sri Chinmoy did something most unusual. He invited Mahiyan to be his doubles partner against Malati and Pratap. This may well have been the first time that Sri Chinmoy had played tennis with a doubles partner. Although Mahiyan did have doubles experience, he was far too stunned by Sri Chinmoy’s invitation to play his natural game and he seemed to remain paralysed near the net. As a result, they lost many points in the opening games, but recovered to win 3-2. Afterwards, Sri Chinmoy played Malati and Pratap alone, defeating them 6-1. On this day, he had played a grand total of 40 games, of which he had won 27.

On August 15th, Sri Chinmoy recorded 16.9 seconds in a 100-meter race. Transferring to the tennis court, he defeated Mahiyan 6-4. In the afternoon, he again practised his service, this time serving 50 balls from each side of the court. His first game of the afternoon was against Databir and Mahiyan. He lost 4-6, but went on too defeat the next doubles pair 6-1. Sri Chinmoy had a knack of not telegraphing his intentions to his opponents, so that they could seldom anticipate his shots. And a moment of indecision was generally all he needed to liquidate an opponent.

By the next day, Sri Chinmoy was in peak form. It took him just 35 minutes to beat Mahiyan 6-4, and 21 minutes to beat a doubles team that included Anugata. Of all the players he faced, Anugata’s serve gave him the most joy. On one occasion, he said, “Anugata’s serve sends me to heaven!” Definitely, his medium stature affected the power of his own serve. Both Mahiyan and Anugata stand well over six feet tall.

During the afternoon of August 17th, Sri Chinmoy played 40 games in succession against various doubles teams before a gallery of 450 spectators, conceding only 9 games to his opponents. The following day, he played 30 games, winning 20. On August 19th, he played 26 games, winning 17. Once ignited, his appetite for tennis was boundless. It seemed that he would prefer to stay all day and night at the court, if it were possible. On August 20th, he defeated his students 25-11 and, on August 21st, he played a grand total of 78 games, winning 55. In spite of the score in his favour, these were closely fought matches, studded with long rallies and superb shots from both sides. It was point and counter-point and the emotions of the spectators fluctuated accordingly.

On August 23rd, Sri Chinmoy defeated his students 44-12. This was the last round of tennis for a number of days as other commitments took its place. Moreover, Sri Chinmoy had been turning his attention more and more to sprinting, working through various drills on the narrow driveway outside the court. He practised with and without spikes. He also began to wear a special mouthguard which had been custom-designed by his dentist. He believed this would significantly increase the speed of his legs and arms. Sri Chinmoy even tried wearing the mouthguard for a number of tennis games and found that his strength and flexibility were greatly improved. It was one of Sri Chinmoy’s traits that he was always keen to try new techniques or training methods which would give him an edge.

Towards the end of August, Sri Chinmoy attended the US Open to watch one of his favourite players: John McEnroe. This gave him fresh inspiration in his own tennis. The very next day, he won his matches against his students 19-1. However, because of his strict diet, he complained of not having any life-energy. Shortly afterwards, he sprained his leg doing a 400-meter sprint and was forced to spend considerable time working out on exercise equipment while his leg healed.

September 2nd was Mahiyan’s last day in New York. Sri Chinmoy did some sprint training in the morning, covering 100 meters comfortably in 16.7 seconds and 400 meters in 86.75 seconds. He then played many consecutive games with Mahiyan, farewelling him with splendid shot-making.

Following Mahiyan’s departure, Sri Chinmoy continued to play for many hours each day, often extending far into the evening. During one memorable encounter with Anugata and Databir on September 6th, Sri Chinmoy cunningly manoeuvred both players into the same box, then cried “Flee!” Finding themselves huddled together, they could only watch helplessly as Sri Chinmoy hit a hard topspin forehand into the opposite corner.

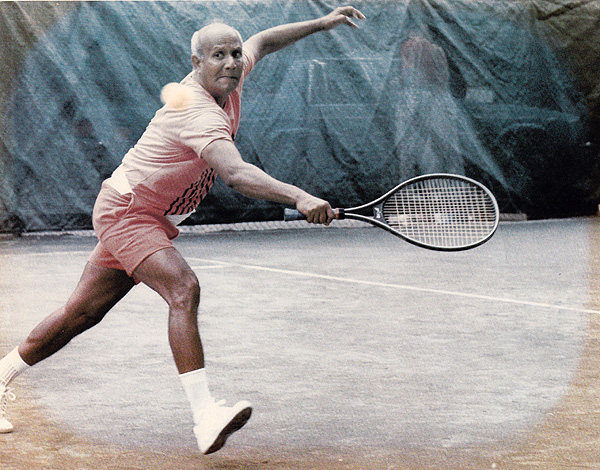

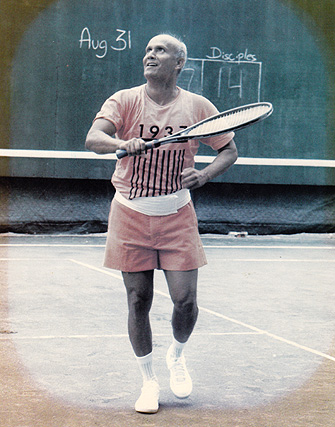

Sri Chinmoy keeps his eyes on the ball as he reaches for a backhand shot.

In the throes of a hard-fought point.

The joy of the game.

About reading the play during a game, he commented: “Even before they serve, I have made up my mind where I shall return it. Whether I shall do a lob or forehand or backhand, I know – unless it is an ace or impossible position. But usually I know already, so I don’t have to waste time deciding.”

One of the shots that delighted Sri Chinmoy most, especially at night, was a sky-high lob. Often his lobs would soar beyond the circle of electric night into the blackness of the night. This understandably caused many mental problems for the player on the other side of the net, trying to time a smash when he could scarcely even see the ball.

On September 8th, Sri Chinmoy played barefoot. His aim was to toughen up his feet so that he might one day run barefoot, as he used to do when he was a youth in India. Between games he sprinted in short spurts across the court or jumped up and down on his toes. He played without shoes again the next day, this time less gingerly, and won 11-5.

Within a few days, this multi-talented champion had put his tennis to one side as he intensified his preparations for the World Masters Games in Puerto Rico.

– End –

Copyright © 1984, Vidagdha Bennett. All rights reserved under Creative Commons license.

Endnotes:

1 For more information on Pat Du Pré see: Wikipedia

2 For a photo of Mayer in action in 1973, visit: Stanford Photo

3 For more information on Borg see: Wikipedia