In the fall of 1919 Albert Einstein received confirmation that light rays passing by the sun’s gravitational field were bent, and the degree of their deflection was in accordance with the predictions he had made from his General Theory of Relativity four years earlier.

In the course of a discussion with a student he was asked what he would have said if there had been no such agreement. Einstein’s reply? “Da könnt’ mir halt der liebe Gott leid tun. Die Theorie stimmt doch.”1 (Then I would have to pity the dear Lord. The theory is correct anyway.)

Einstein’s statement, far from scientific over-confidence, was merely confirming his innate faith in a universal order — the fact, as he once put it, that, “God does not play dice.” Nevertheless, his remark seemed to characterise the scientific method as an expression of a self-evident truth, that the universe can be described in terms of a system of immutable laws which yield neither to man nor God.

There is recent evidence to suggest, however, that the grand hypothesis upon which the scientific method has been founded may be in need of review.

We are apt to believe that any revolution in science must necessarily come from the frontiers of research, that the world of everyday experience is solidly confirmed as functioning within well-defined physical parameters.

It seems ironic that the scene of this new challenge comes not from the laboratories at MIT2, the space observatories of NASA3 or the linear accelerator at CERN4, but the suburbs of New York City where, day after day, many have witnessed an occurrence that may be regarded as violating the laws of natural science.

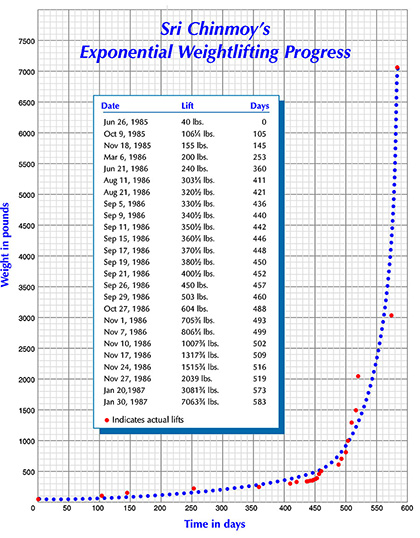

On August 21, 1986, Sri Chinmoy, a 55-year-old Indian spiritual master, proceeded to lift a weight of 320½ pounds (double his own body weight) above his head, using only one hand.

The chronicle of his rapid progress reveals a fascinating story of the possibilities of human achievement.

The single-arm weightlifting efforts of this slightly-built, self-effacing man of peace, who has astounded the best weightlifters in the world, began just a little over a year earlier with a lift of 40 pounds on June 26, 1985 and within four months he had exceeded 100 pounds (106¼ lb. on October 9).

Up and until this point Sri Chinmoy had hoisted weights from the ground to a fully extended position above his head, by adapting a standard weightlifting technique called the ‘deadlift’. But because of a chronic back injury, he found it increasingly difficult to bend and it soon looked as though Sri Chinmoy’s weightlifting accomplishments might be at an end. However, an Australian student of his, Unmilan Howard, came up with an idea to suspend the weights in a completely enclosed rack with looped iron support guides, allowing Sri Chinmoy to start his lifts at shoulder height.

The ‘cage’ as it was affectionately known also added an important safety factor to his new method of lifting. The weights were now getting so dangerously large that one slip could have easily resulted in severe injury. With this innovative device, the huge weights if dropped would be caught by the metal support slings.

Sri Chinmoy was breaking new ground and many traditional weightlifters at first looked sceptically upon Sri Chinmoy’s new technique — until they saw the results:

By November 18, 1985, he had lifted the equivalent of his own body weight (155 pounds). On March 6, 1986, he had reached the 200-pound mark; by June 21, less than one year after he began, he could lift 240 pounds; and then on August 11, with his 212th attempt, he surpassed the 300-pound mark with a lift of 303¼ pounds. These were not easily won victories but they showed that he was now well on his way to lifting twice his own body weight. And on August 21, with the lift of 320½ pounds, he did just that.

Sri Chinmoy would supplement his heavy schedule of weight training by using various exercise machines at all hours of the day and night. He also included traditional methods of strengthening in his daily routine. At one time he recorded 2,230 push-ups in less than one hour; such was the dedication he displayed towards reaching his goal.

On September 5, Sri Chinmoy lifted 330½ pounds; on September 9, 340½ pounds; and September 11, 350½ pounds. Then, in two-day intervals from the 15th to the 19th of September, he proceeded to lift 360¼, 370¼ and 380½ pounds respectively. His next lift, against all predictions of athletic progress and unprecedented in weightlifting circles, was 400½ pounds on September 21.

As every athlete knows, there comes a point when approaching optimum performance, any increase in training will produce only a marginal increase in results. Given his age and experience, one would rightly assume that Sri Chinmoy’s lift of 400½ pounds would indicate that he was nearing his peak.

Apparently not. With a seemingly total disregard for the diminishing returns of physical performance, he decided to increase the weight of each progressive attempt by 50-pound increments. On September 26, he lifted 450 pounds and three days later, on September 29, he raised 503 pounds, not once but six times.

At the very beginning of Sri Chinmoy’s weightlifting journey, as he struggled to hold up 40 pounds, even though he had set no limit for himself, not many could have predicted his future achievements. But as the weights mounted an ultimate goal began to emerge — his aim was to lift 700 pounds.

Within one month, on October 27, the intermediate mark of 604 pounds was reached and 5 days later, on November 1, he surpassed his goal with a lift of 705¾ pounds.

In the 16 months since he started training he had managed to achieve what no man on earth had done before — to lift, with one hand, more than four times his own body weight.

As a philosopher and teacher, Sri Chinmoy has written hundreds of books — 700 in fact. Possibly this is why 700 pounds held such significance for him. Yet it came as no surprise to those who had read his writings on self-transcendence that “today’s goal” would become “tomorrow’s starting point”. Never one for mere dogma or platitude, he takes each new challenge as an opportunity to offer something tangible in the form of inspiration to mankind.

It now seemed as though his former achievements were mere preparation. He went on to lift 806¼ pounds on November 7 and on November 10 the 1,000-pound mark was surpassed with a lift of 1,007¾ pounds. By November 17, he had lifted 1,317¾ pounds and on November 24, 1,515¼ pounds.

One can perhaps be forgiven for harbouring reservations.

How is it physiologically possible for a man of such slight build (5’8” high and weighing 159 lb.) to lift weights never dreamed of?

“He has surpassed anything and everything that any weightlifter has ever done throughout the world. As far as I know, 600 pounds is more than the greatest weight anybody has ever held with one arm or two arms; 1,300 pounds is utterly incomprehensible.” — Jim Smith (BAWLA)5

How, at the age of 55, with just 16 month’s training and no prior background in weightlifting, is it possible to achieve, sustain and transcend world-class performances?

“If he can lift that much weight in that short a time he can inspire me to break that long jump record. I’m going to use his inspiration to help me reach my milestone.” — Carl Lewis (Olympian)6

How is it possible for the tendons and bones in the wrist and elbow, the shoulders and the spine to bear up under a force of such weight?

“The amount of weight Sri Chinmoy is doing is so unbelievable! I have never heard of anyone doing so much weight. It is so much pressure on the shoulders and lower back. It is unbelievable pressure on the body.” — Cliff Sawyer (AAU)7

“This man is of Godly strength. He is truly amazing. It is humanly impossible for the body’s joints to even budge this kind of weight. Just to support this kind of weight in any way is a miracle.” — Bill Pearl (former Mr. Universe)8

No, this is not a trick or some type of sideshow levitation act. There are no strings or misleading camera angles. Sri Chinmoy does actually lift these weights.

The effort is recorded well in the strain of trembling muscles, the involuntary screams of will, in the look of terror concentrated in his eyes and the bewildered agony on his face. It is etched within the sudden expression of relief, as the shifting mountain of metal is released to its inertial abode. It is revealed in all its sweetness in the faint smile of victory lying deep and silent beneath the mounting layers of fatigue.

He leaves his weightlifting room in utter exhaustion only to resume moments later, this relentless battle with inconscient matter. In one day he has been known to lift over 228 tons, (457,600 pounds to be exact) with repetitions of various size weights in training.

He is able to do this not through physical power but through spiritual power — the result of his years of intense prayer and meditation.

“The source of power,” he says, “is infinitely greater than the physical strength that any human being can have.”9

He describes “physical energy” as having “only one source, and that source is spiritual energy. As long as we are conscious only of the body, we are not aware of this, but when we go deep within through meditation, we see that spiritual energy is the source of physical, vital and mental energy.”10

“There are countless people on earth who do not believe in the inner power, the inner life. They feel that the outer strength and the outer life are everything. I do not agree with them. There is an inner life; there is spirit, and,” he states with experiential certainty, “my ability to lift these heavy weights proves that it can work in matter as well.”11

Outwardly Sri Chinmoy’s modest physical capacity would appear incapable of lifting such enormous weights, but he explained the simple method behind his success quite candidly at a press conference in Queens, New York, on August 12th, 1986: “I am trying to inspire people who are not praying and meditating. I am telling them that everybody has a vital, everybody has a mind, everybody has a heart, everybody has a soul. Only they are not using the help of these members of their family the way I do. Otherwise, if I had to depend entirely on the physical, I could do nothing. My bicep is not even 14 inches, whereas the bicep of other weightlifters is 21 or 22 inches. My calf is not even 13½ inches, and theirs is 20 inches. Their muscles are gigantic compared to mine. It is absurd! So if I can lift as much as I do, that means that I am taking help from within me. My other friends — the vital, the mind, the heart and the soul — are helping me from within.”12

Very early in his weightlifting career, Sri Chinmoy was asked, “how much of heavy lifting is mental preparation and how much is physical preparation?” He went on to answer this in a surprisingly unorthodox manner: “The great champions are of the opinion that 70 or 75 per cent of weightlifting is mental preparation. But in my case, 99 per cent is God’s Grace and God’s Compassion. For the remaining one per cent, three quarters is mental preparation and one quarter is physical preparation.”13 And even this fractional personal input, Sri Chinmoy maintained, was wholly due to God’s Grace and God’s Compassion.

By late November an amount of weight, exceeding 2,000 pounds, hung on the bar — still, lifeless, inert — waiting for a touch of inspiration. Regard this how you will, but before discussing further the source and manifestation of this well-documented phenomenon it might be appropriate to address some of the major concepts in western philosophical thought regarding the way we view our universe and compare them with corresponding philosophical ideas from the East.

***

Possibly the most far-reaching and ill-founded premise in determining our locus of comprehension is that the analytical mind, in its application to the scientific method of enquiry, has the means to subsume the totality of universal experience and as such lays singular claim to the lofty office of sole arbiter of objectivity.

The existence of any experience beyond the mind is, by the scientific community, at best admitted and regarded as subjective or completely dismissed as self-deception. The classic lines from An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding by David Hume (1711-76) are still echoed by many contemporary academics:

“Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.”

The scientist accepts a priori that the world is governed by definable physical laws and rejects any notion of experience beyond the material conditions — science is, by its own definition, a closed system.

The play of subtle forces which saints and mystics of all religions have purportedly explored for millennia, have remained unfamiliar to secular man; and even though, at times, these forces have impacted dramatically upon his world, they have eluded plausible causal definition.

The occasion to observe such interactions between matter and spirit does not readily present itself — the manifestation of spiritual forces seems so transient in comparison to the overwhelming permanence of the physical phenomena in which we live. Witnessed by the few, misinterpreted by the many, these infrequent occurrences pass, in time, from hearsay to folklore and legend.

But when the scientific world comes face to face with a phenomenon it cannot explain, a baffling occurrence that defies understanding, where the common utility of empirical reasoning ceases to account for experience, it raises the question — is the mind itself, which has served us so well in expanding our knowledge of the universe, now limiting our approach to a deeper truth?

While the main body of science is continually being renewed, our system of modern scientific enquiry has changed little since the days of Hume.

The particular has given way to the general. Newtonian physics has been encompassed by the broader theories of Albert Einstein; and Aristotelian logic has been embraced by the new logic of Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead. Yet one fundamental precept has not changed — our awareness of universal experience remains bound by the domain of the mind.

To accommodate these new challenges, a complete re-centring of scientific perspective must take place. A translation of the co-ordinates we use to locate our understanding is necessary for further progress.

Einstein saw more clearly than most, the manner in which our human consciousness is evolving. “The mind,” he declared, “can proceed only so far upon what it knows and can prove. There comes a point where the mind takes a leap — call it intuition or what you will — and comes out on a higher plane of knowledge, but never can prove how it got there. All great discoveries have involved such a leap.”14

This intuitive plane of which Einstein spoke is confirmed by Sri Chinmoy himself — it is indeed a higher level of consciousness, a plane of knowledge above that of the ordinary mind that occasionally reveals itself to receptive thought: “A scientific achievement need not be from the mind, not even from the intellect; the greatest scientific achievements come directly from the intuitive plane.”15

“Intuition is a very high step in the spiritual evolution of the mind,”16 but it is only one of a number of higher levels that the human consciousness can attain to.

He explains further: “We start with the physical mind — that is the mind that is governed by the physical — which is the lowest mind. In the physical mind it is all obscurity, impurity, imperfection, bondage, ignorance and limitation. This mind sees each object separately, plus it doubts the existence of each object. Real doubt starts here in the physical mind.

“A little higher is the intellectual mind, which deals with abstractions and more sophisticated thoughts. Doubt, confusion and contradiction reign here.

“Next we come to the vacant mind. The essence of formless ideas can be perceived here. But thought cannot enter into existence in this mind. Therefore, it has no opportunity of being assimilated and transformed.

“Next is the calm mind. It is like an expanse of sea. Wrong thoughts can enter here but they cannot grow in this calm mind. If bad thoughts enter, they are assimilated into good thoughts and divine willpower.

“Then comes the higher mind. In the higher mind thoughts are elevating, constructive, subtle and progressive.

“Next is the inner mind. In the inner mind the knowledge of creative thought and the wisdom of the inner light play together.

“Then there is the intuitive mind. The intuitive mind is the Vision-mind. From it we get dynamic and creative revelation, but not in the form of thoughts as we know them in the physical and intellectual minds. With the intuitive mind we see multiplicity in a creative form. With intuition we see all at a glance. We can see many things at a time; we see collective form.

“Then comes the overmind. Here form starts, multiplicity starts in an individual form. God is in infinite forms in the overmind.

“Then comes the supermind, where creation starts. The supermind is not something a little superior to the mind. No. It is infinitely higher than the mind. It is not the ‘mind’ at all, although the word is used. It is consciousness that has already transcended the limitations of the finite. There is no multiplicity, no diversity here, but a flow of oneness. Everything in the supermind is one, whole, complete.”17

These inner states of being have remained unexplored by western science because, in terms of a physically perceptible reality, very little of the inner universe is ever manifested. Knowledge, peace, power and even the more remote qualities like bliss, light or grace are essentially boundless; yet it is only in the inner world that the term infinity has any real meaning.

Through meditation the physical consciousness can gradually become aware of the inner reality. In the highest states of meditation, the ultimate source of knowledge can be experienced. Since there has never been a corresponding western term for this state of consciousness, it is known only by its Sanskrit nomenclature as ‘nirvikalpa samadhi’.

Christopher Isherwood, in Ramakrishna and His Disciples, a biography of the great 19th-century yogi Ramakrishna, proffers his explanation of this rarefied state:

“Like all but the merest handful of people alive in the world today, I have never come anywhere near experiencing it. And even those who have experienced it have had great difficulty in speaking of their experience. One may say, indeed, that it is by definition indescribable. For words deal with the knowledge obtained by the five senses; and samadhi goes beyond all sense-experience. It is in its highest form a state of total knowledge, in which the knower and the thing known become one … Outwardly samadhi appears to be a state of unconsciousness, since the mind of the experiencer is entirely withdrawn from the outer world … But, in fact, samadhi is a state of awareness unimaginably more intense than everyday consciousness.”

Naturally, the description of such states, in ordinary terms, remains awkward even for those who have experienced them. Nevertheless, for spiritual masters like Sri Chinmoy, these higher states of consciousness are first-hand knowledge, as observable and empirically verifiable as any scientific fact.

The implication here is obvious: it is not the mind that is at the centre of all universal experience, but consciousness. It is not an easy idea to accept, especially for those of us living within the comforting limits of the mind. Yet it is an inevitable step we must take. We cannot for the sake of our own convenience cling to a Ptolemaic world-view when faced with the Copernican cosmos.18

If we remain in the mind we cannot fail to agree with the existentialist view of Jean-Paul Sartre: “Things are entirely what they appear to be and behind them … there is nothing.”

There is, thankfully, another side to reality.

In a superficial way we identify and classify the finite features of our existence with the mind. “But,” says Sri Chinmoy, “you are not the body. You are not the senses. You are not the mind. These are all limited. You are the soul, which is unlimited. Your soul is infinitely powerful. Your soul defies all time and space.”19

He explains how it is possible to transcend the limits of the mind: “In order to realise that you are not the mind, that you are the soul, first you have to go beyond the mind. There are two ways to do this. One way is to go up through the various levels of the mind and then pass beyond. The other process is to bring down Light from the higher planes into the mind. When higher Light descends into the mind, at that time the mind does not remain an obstacle to our inner realisation of our conscious oneness with our soul’s existence.”20

To achieve this “conscious oneness”, meditation is necessary. Sri Chinmoy describes the process as a natural, progressive development of the human quest: “Meditation is dynamism on the inner planes of consciousness. … When we meditate, what we actually do is enter into a deeper part of our being. At that time, we are able to bring to the fore the wealth that we have deep within us.”21

Mediation and thinking, even what we call ‘deep thinking’, are not the same. According to Sri Chinmoy, “Thinking and meditating are absolutely different things — totally, radically different things. … The aim of meditation is to free ourselves from all thought.”22

“In meditation,” he explains, “we should not give importance to the mind. If there is no information coming, it is good. Real meditation is not information; it is identification. The mind tries to create oneness by grabbing and capturing you and this may easily make you revolt. But the heart creates oneness through identification. The mind tries to possess. The heart just expands and, while expanding, it embraces.”23

The ‘heart’ Sri Chinmoy speaks of is not the physical organ but the spiritual heart, a much subtler part of our being that identifies with the higher feelings of love, compassion and oneness. “The domain of the spiritual heart,” he says, “is infinitely higher and vaster than that of the very highest mind. Far beyond the mind is still the domain of the heart. The heart is boundless in every direction, so inside the heart is height as well as depth.

“The higher you can go, the deeper you can go. And again, the deeper you can go, the higher you can go. It works simultaneously.”24

Blaise Pascal, the great 17th-century mathematician and philosopher, caught a glimpse of this differentiation in his book Pensées when he wrote: “The heart has its reasons which reason does not know.”

“If you meditate in the heart,” says Sri Chinmoy, “you are meditating where the soul is. True the light, the consciousness of the soul permeates the whole body, but there is a specific place where the soul resides most of the time, and that is in the heart. I am not speaking of the human heart, the physical heart which is just another organ. The spiritual heart is located in the centre of the chest, in the centre of our existence. If you want illumination you will get illumination from the soul, which is inside the heart.”

Sri Chinmoy is, by his own definition, an ultramodern spiritual master. His unique path to self-realisation has taken on many positive aspects and perspectives of western culture yet his spiritual insight remains rooted in the philosophical traditions of ancient India.

The essence of India’s spirituality can be traced back over 4,000 years to the Vedas, the oldest documents known to mankind. They sprang from the oral spiritual tradition of India’s hoary past and were later written down and expanded upon by other great sages — seers who had realised within their own lives the existence of a vast universal reality, of which the mind conceived a very limited portion. Consciousness itself, they said, was infinite and what the mind could retain was only a fleeting awareness of transient forms.

***

Aside from these exalted revelations, the ancients of India also gave the world the indispensable mathematical concepts of infinity and zero, and what later became known as the Arabic numerical system — our modern number line25. The works of Plato and Pythagoras, too, had their inspiration in Vedic thought.

Just as the concept of the atom lay dormant for more than 2000 years from Kanada (India) and Democritus (Greece) to Dalton, so the theories of the origin and evolution of the universe as expressed in the Vedas have waited patiently for modern scientific interpretation. The Big Bang theory, first propounded by Georges Lemaître, and more recently expanded upon by the work of theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking and mathematician Roger Penrose, reflects the Vedic notion of an expanding universe emanating from a singularity. Though couched in the language of their times, there is an essential equivalence of perception of a timeless universal truth.

Penrose captured the view of universal discovery through mathematics with his words: “I have a sense of uncovering things that were there all the time … I am awfully tempted to use God in such a setting because one is kind of revealing God’s work.”26

Another of history’s great discoverers was trying to do the same thing, although some of his contemporaries didn’t see it that way.

In 1859, Charles Darwin published a book entitled On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, which changed the way we viewed the human race. We saw ourselves no longer as static creatures but as beings capable of transcending our own limitations, beings on a journey of evolution. Darwin’s grand theory detailed the process of physical evolution which, as it happened, remarkably paralleled the Vedic idea of the evolution of consciousness: As physical life has evolved from lower to higher forms, so too has consciousness evolved, through the primitive impulses of single-celled protozoa, to the human experience of feelings and perceptions, to the ultimate enlightenment of universal knowledge.

The ancient seers knew that that which preceded creation, or the manifestation of the physical universe, was a spiritual reality. And Sri Chinmoy, echoing the voice of timeless Indian wisdom, poetically describes the very process of creation: “The Self-Division of the Supreme proclaims the birth of creation. Creation is the descent of Consciousness.”27

The physical is the outermost layer in the manifestation of an essentially spiritual universe — a finite measure of an infinite multidimensional cosmology.

Vedic knowledge passed down through the centuries in its purest form through the lives of those who had realised its spiritual truths and by their own account verified and expanded upon its perimeters.

In one sense Sri Chinmoy can be seen at the forefront of this hallowed tradition. In essence he is, but in practice he is far removed from its antiquity. Whereas the ancient Himalayan cave dwellers contemplated the universal mysteries in solitude, rejecting contact with the secular world, Sri Chinmoy is very much involved with humanity’s cry for perfection.

In April 1964, Sri Chinmoy arrived in New York from his native India. He had spent 20 of his 33 years there in a spiritual community, practising meditation and related inner disciplines as well as track and field sports. An odd combination, one may think, but this unlikely synthesis of inner reflection and outer activity laid the foundation of his unique contribution to twentieth-century thought — the philosophy of self-transcendence.

“Our goal is always to go beyond, beyond, beyond. There are no limits to our capacity because we have the Infinite Divine within us,” he says. “When you transcend any aspect of yourself your spiritual qualities grow and expand. Now you see what is true for all human beings: We are all truly unlimited if only we dare to try and have faith.”

It is a theme, which is repeated in all of Sri Chinmoy’s endeavours. Weightlifting is for him a relatively new activity, which has been assimilated into an already busy life as a writer, artist and composer.

True to the request of what he terms an “inner voice” or his “Inner Pilot” he has followed his creative inspiration sleeplessly and at times with great personal sacrifice to produce one of the most extensive bodies of artistic work in history. The works of Milton, Picasso and Schubert, considered among the most prolific in their fields taken collectively, do not equal Sri Chinmoy’s output in magnitude.

He is, in the real sense of the term, a renaissance man, touching each area of human achievement with the new light of inspired genius. The contemporary conductor and composer, Leonard Bernstein, expressed it similarly: “You are a miraculous model of the abundance in the creative life that we lesser mortals seek … I can only hope that I may someday participate in that cosmic fountain of stillness and profound energy which you inhabit.”

When approaching Sri Chinmoy physically, one senses this subtle world of power in which he is absorbed. He responds with ease to conversation and circumstance but, for all the while, there is a warm detachment in his manner — a reminder that he is at once possessor and possessed of something infinitely more magnificent.

At times he will offer a smile of gratitude more engaging than that of one whose life has just been saved. At other moments, his eyes focused somewhere between the finite and the infinite, he bears the intensity of a man on the point of great discovery, entrusted with an irrevocable responsibility to the world.

He has the confidence and patience born of his private encounters with the beyond. And like Christopher Columbus, who spoke of strange new lands across the seas, or Galileo Galilei, who gazed upon the wondrous movements of the heavens, he must inevitably suffer the arrows of a sceptical world. Yet there is no dint in his resolve. He replies to intellectual conservatism with the magnanimity of a visionary:

“We have to go forward with new ideas. Every day science is making new discoveries. If we go on, with the same old book, although it may be a good book, an excellent book, it becomes boring. So if someone finds a new book, written in a different style, with different words then everybody is so delighted.”28

And strives to shine a light beyond the artificial borders of human discovery: “Anything that has been done in the past is recorded and is well appreciated. If a new idea or a new goal enters into a human being, then he becomes the pioneer in that particular field. When people normally speak about an era, they are talking about a period of time when an individual or a group of individuals has achieved certain things. An era depends entirely on the individual achievement or collective achievement that occurred during a number of years. But I see an era in terms of vision. I take an era as the vision of human beings for a certain period in life or in history. If somebody comes with new inspiration and new aspiration, he opens a new door for mankind to look forward and upward and offers a new vision. So ‘new era’ to me means the opening of a new door in our consciousness that allows us to go forward rather than stay with the past. Again, if there is something helpful in the past, we shall not discard it. The old way or traditional way or, let us say, the conventional way, we are not discarding. Because it is helpful and beneficial, we shall accept it. But if somebody discovers something new — a new method, a new approach to reality — then definitely he is embarking on a new discovery. And this new discovery itself brings in a new era.”29

***

On November 27, 1986, Sri Chinmoy recorded what seemed to be his ultimate achievement — a lift of 2,039 pounds.

In mid-December Sri Chinmoy left New York for a concert tour of South America and for one month he was restricted to training with small stacks of portable weights. Still, he returned home with renewed enthusiasm, determined to lift more than 3,000 pounds.

But under the strain of this massive weight, the solid iron dumbbell-bar itself had begun to bend. It was obvious to everyone at that point, that a degree of radical engineering had to be adopted for Sri Chinmoy’s expedition into the uncharted realms of weightlifting to proceed any further.

The idea of extra supports had been discussed but, with little time to calculate all the stresses involved, Unmilan Howard had to trust his intuition as a metalworker to provide the most practical solution. He quickly set about constructing a relatively lightweight tube-metal truss that would sit on top of the bar, providing enough structural integrity to keep it straight and rigid as the 100-pound plates were suspended from it. It worked! On January 20, 1987, Sri Chinmoy successfully lifted 3,081¾ pounds.

The final lift in this exponential climb to the stars was now just days away.

The constraint was no longer a matter of Sri Chinmoy’s fitness, but the physical time needed to construct the enormous supports which would have to stretch across the 15-foot length of the bar, to hold the expansive mass in place. And, there was another problem — the improvised gym on the ground floor of Sri Chinmoy’s house in Queens, N.Y. had outgrown its surroundings in both weight and dimension. A small team of builders and engineers worked around the clock on the project. Much of the room was cleared of other exercise equipment and the basement ceiling was reinforced with steel floor-jacks to support the gigantic apparatus that was to be installed.

Finally, just before midnight, one cold January New York evening, the structure was complete. Sri Chinmoy would not only have to raise the sixty-eight solid 100-pound plate weights, but also the supporting truss and bar, which themselves weighed an additional two hundred pounds. At 1.25 a.m., January 30, 1987, on his 3rd attempt, Sri Chinmoy lifted 7,063¾ pounds. Of the five attempts (1:03 a.m., 1:13 a.m., 1:25 a.m., 1:37 a.m. and 1:50 a.m.) the final three were completely successful — a combined weight of over 10 tons, held aloft by one human arm and an unfathomable will.

Jim Smith, from the British Amateur Weightlifters Association, who had been following Sri Chinmoy’s progress since he began, put it simply: “Sri Chinmoy is causing us to throw all our current beliefs in physics out the window. Sri Chinmoy is wrecking what we’ve always regarded as normal laws. Sri Chinmoy is rewriting the physiology books all over again!”

To many, Sri Chinmoy’s feats will forever remain inconceivable. They are challenging to all we hold valid in our traditional western view of the universe. Yet these undeniable achievements, if viewed with the light of consciousness, free from mental reinforcements and constraints, will undoubtedly one day form the basis for a new identification between our inner and outer lives.

On June 26th 1988 Sri Chinmoy, stepped on stage at Julia Richman Auditorium in Manhattan and demonstrated the ‘impossible’.

In a continuous exhibition of weightlifting, witnessed by the public and hosted by renowned weightlifting expert Bill Pearl, Sri Chinmoy lifted a variety of massive weights using different styles: one-arm, two-arm, seated calf-raise and standing calf-raise lifts. At times, as substitutes for the iron-plate weights, various groups of people (as many as 30 individuals plus equipment) were positioned on platforms. He lifted them in the same manner. The spectacular conclusion to the weightlifting display came when Sri Chinmoy, using only one arm, hoisted Bill Pearl (229 lb., including platform) overhead, momentarily suspending the Master of Ceremonies high in the air. The cumulative weight Sri Chinmoy lifted during the event was in excess of 20 tons.

Bill Pearl summed up the feeling of every person present that evening: “What this man has accomplished in weightlifting is phenomenal. He makes no claims, he needs no claims. That Sri Chinmoy lifted over 40,000 pounds in one hour and 45 minutes speaks for itself.”

Yes, Sri Chinmoy raises weights but he has also raised many questions regarding our scientific attitudes.

As the plane of intersection between the physical universe and the spiritual universe widens, we are drawn inevitably to address new concepts and to admit possibilities greater than the current scientific mandate will allow. Real progress in science will now depend not so much on improving research techniques or refining data analysis, but on broadening its philosophical base. The very fundamentals upon which the scientific method itself has been founded must be reassessed.

Sri Chinmoy has thrown open the door to a new dimension of discovery. It is a profound revolution indeed to consider a world-view where the material and the spiritual are one, where the highest divinity can be realised in and through the physical, where mankind itself is evolving towards an unlimited consciousness.

We have sent our messages to the stars, we have conquered the forces of the atom, but still we do not know ourselves. Who is this race of beings who would proclaim their dominion over the entire universe yet have sought in vain for their own identity? Even in the face of the enormous scientific progress of the last centuries, the words of the immortal Sir Isaac Newton are as relevant today as they were over 250 years ago:

“I do not know what I may appear to the world; but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.”30

Herein lies a challenge to us all, scientist and non-scientist alike: to leave the shore of our preconceptions and fears, to set out across the great ocean of truth in search of knowledge beyond the limits of the mind, to reach what Sri Chinmoy so prophetically refers to as the “Golden Shore of the ever-transcending Beyond.”

— End —

Endnotes:

1 Abraham Pais, Subtle Is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford University Press, 1983, p.30.

2 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

3 European Organization for Nuclear Research

4 National Aeronautics and Space Administration

5 Registrar of Records, British Amateur Weight Lifters’ Association

6 Winner of four gold medals in track and field at the Los Angeles Olympics; World record holder for the long jump (indoors and at sea level)

7 AAU Physique Chairman and former Arm Wrestling Champion

8 Five-time Mr. Universe; World’s Best Built Man of the Century

9 Sri Chinmoy, Soul-Illumination-Shrine, Body-Preparation-Temple, Part 1, Agni Press, 1985

10 Sri Chinmoy, The Outer Running And The Inner Running, Agni Press, 1974

11 Sri Chinmoy, Aspiration-Body, Illumination-Soul, Part 1, Agni Press, 1993

12 Sri Chinmoy, Aspiration-Body, Illumination-Soul, Part 1, Agni Press, 1993

13 Sri Chinmoy, Soul-Illumination-Shrine, Body-Preparation-Temple, Part 1, Agni Press, 1985

14 Ronald W. Clark, Einstein: The Life and Times, Avon, Reissue edition (1999), p.622.

15 Sri Chinmoy, Art’s Life And The Soul’s Light, Agni Press, 1974

16 Sri Chinmoy, Mind-Confusion And Heart-Illumination Part 1, Agni Press, 1974

17 Sri Chinmoy, Mind-Confusion And Heart-Illumination Part 1, Agni Press, 1974

18 Ptolemy’s world-view was based upon a geocentric model, in that earth was considered to be at the centre of the universe and all other objects circled around it. This theory held sway for 1,400 years until the 16th century, when Copernicus presented a fully predictive mathematical model for a radically different heliocentric system whereby the planets, including earth, rotated around the sun. Interestingly, heliocentrism had been discussed by Indian astronomers in Vedic and post-Vedic texts such as Shatapatha Brahmana, many thousands of years before Copernicus.

19 Sri Chinmoy, Yoga And The Spiritual Life: The Journey of India’s Soul, Agni Press, 1971

20 Sri Chinmoy, Mind-Confusion And Heart-Illumination Part 1, Agni Press, 1974

21 Sri Chinmoy, Meditation: God’s Duty And Man’s Beauty, Agni Press, 1974

22 Sri Chinmoy, Mind-Confusion And Heart-Illumination Part 2, Agni Press, 1974

23 Sri Chinmoy, Mind-Confusion And Heart-Illumination Part 2, Agni Press, 1974

24 Sri Chinmoy, Flame Waves, Part 5, Agni Press, 1975

25 The decimal number system, with the inclusion of zero, was first introduced into Europe by Fibonacci (Leonardo of Pisa) in 1202 A.D.

26 Roger Penrose, The Emperor’s New Mind, Oxford University Press, 1989

27 Sri Chinmoy, Eternity’s Breath, Agni Press, 1972

28 Sri Chinmoy, Aspiration-Body, Illumination-Soul Part 1, Agni Press, 1993

29 Sri Chinmoy, Aspiration-Body, Illumination-Soul Part 1, Agni Press, 1993

30 Sir David Brewster, Memoirs of the Life, Writings, and Discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton, Volume II. Ch. 27., 1855

This article was originally written in 1987. Later references have been added in this version.

Copyright © 2008, Animesh Harrington.

All rights reserved under Creative Commons license.