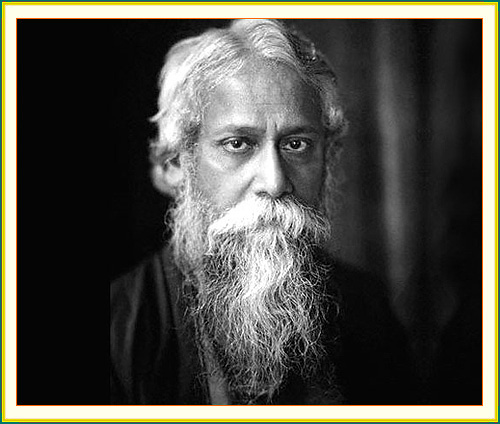

Rabindranath Tagore

রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর

Bengali poet, novelist, playwright, composer and painter.

Awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913.

|

||

|

Released on the occasion of

Rabindranath Tagore's 150th birth anniversary 7 May 1861 — 7 May 2011

|

|

|

||

|

The author,

Nolini Kanta Gupta. |

The translator,

Chinmoy Kumar Ghose. |

|

“Nolini Kanta’s contribution to Bengali literature is unique,” so said Rabindranath Tagore in 1936. It is perhaps appropriate then to re-release this significant selection of eight essays by the great Bengali savant Nolini Kanta Gupta on various aspects of Tagore’s literature to celebrate the occasion of Tagore’s 150th Birth Anniversary.

The essays were originally written in Bengali and published in assorted Bengali literary magazines. In 1955, Nolini-da requested his young secretary, Chinmoy Kumar Ghose, to translate his writings into English. It was no small task for the 23-year-old who had taught himself English only after he arrived at the Ashram in 1944. Nolini-da presented him with a special Corona typewriter on which to work. It had originally belonged to President Woodrow Wilson’s daughter, Nishtha. Then Sri Aurobindo himself used it, and subsequently Nolini-da.

Chinmoy, as he was known then, completed his assignment to Nolini-da’s immense satisfaction and the essays were published serially in the Mother India, The Sri Aurobindo Monthly Review of Culture. In all, Chinmoy translated more than fifty of Nolini Kanta Gupta’s literary works into English during the period 1955–1964 when he was Nolini-da’s secretary.

Nolini Kanta Gupta was known as the Matthew Arnold of Bengal. His writings have been widely acclaimed in Bengal and his observations with regard to Tagore’s works are both penetrating and profound. These exquisite translations by Chinmoy not only make them accessible to a wider English-speaking audience but also reflect the graceful flow, masterful use of language and subtlety of the original Bengali.

—Vidagdha

CONTENTS

|

|

|

TAGORE THE UNIQUE

It is no hyperbole to say that Tagore is to Bengali literature what Shakespeare is to English, Goethe to German, Tolstoy to Russian, or Dante to Italian and, to go into the remoter past, what Virgil was to Latin and Homer to Greek or, in our country, what Kalidasa was to ancient Sanskrit. Each of these stars of the first magnitude is a king, a paramount ruler in his own language and literature, and that for two reasons. First, whatever formerly was immature, undeveloped, has become after them mature; whatever was provincial or plebeian has become universal and refined; whatever was too personal has come to be universal. The first miracle performed by these great figures was to turn a parochial language and a parochial literature into a world language and a world literature. The second was to unfold the inner strength and the deeper genius of the language to reveal and establish the nature and uniqueness of a nation’s creative spirit as well as the basic principle of its evolution and culture. These two ways, one tending to expansion, the other to profundity, are in many cases mutually dependent and are often the result of a sudden or rapid outburst.

Ballad and folklore are the infant or immature form of a language and literature. Polished and powerful language and literature develop out of that and only subsequently attain their full blossoming. In this respect Dante’s marvel is almost without parallel. The language he used in clothing his poetry was a popular dialect; one among various other popular dialects—this he turned into the language of Italy as a whole, the Italian language as it stood before the eyes of the world. A music and rhythm of a great and lofty consciousness infused itself into the elements that had lain neglected in the dust. The voice confined within the four corners of the household and the village underwent a miraculous change in the mouth of a magician; it became a voice of the universe. And, in a language and a literature that are not so immature but have already attained development and elegance, a creative vibhuti has brought about a second type of transformation. Virgil, Shakespeare, Goethe and Kalidasa did a work of this category. It cannot be said that English was undeveloped or quite rustic before Shakespeare, although the impression of the grandly real, something truly familiar and intimate that Shakespeare evokes in the heart of foreigners is not given by Spencer, Chaucer or even Marlowe. Shakespeare has revealed something of the universal in the very special style he created—here was a diversity, a plasticity, a suggestiveness, a magic all its own.

There is some difference between the history of French literature and that of any other. First, the French language and literature have grown and matured not through a sudden change or a revolutionary transmutation—their growth and development are the result of a slow and steady process of evolution. In English, on the other hand, the sense of growth seems to consist of a rapid change. In the political field, however, the English and the French have pursued quite reversed policies. The battle for liberty by the English continued from precedent to precedent—the French had always to win freedom through revolutions. But the other speciality of the French literary spirit is the fact that there was no single person who had a kind of all-in-all authority,—although in politics, in old France at least, it was often one man’s rule, the tradition of the Roman Imperator, that prevailed. In the literary field among the instances cited we find that each nation had a single person of authority, a specially gifted one who moulded its language and literature by the magic touch of his own genius or made them fully mature and self-sufficient. The French are a very social race—they are proud to be called republican, so it is by the combined effort of many, the contribution of more than one genius, that their language and literature have been formed and enriched. Corneille, Racine, Molière, La Fontaine (or up the stream to Rabelais)—they are a goodly company; among these whom to exclude and whom to include? And yet here too, perhaps only one can be taken as France’s representative spirit. He can be only Racine. Racine embodies in himself, as no other does so completely, the special characteristic of the French and reflects the heart of the French people. What is that characteristic? In one word, the culmination of elegance and sensitiveness. To be sure, this is not the only aspect of the French. Corneille has contributed to another aspect—severity, virility, high seriousness, austere self-control, strictness and bareness. But this may be considered a special quality of a branch line, as it were, of the French language and literature, as if it was an acquired capacity, the sign of a growth towards a greater possibility—but in regard to the other it may be said that what Racine is is the French language and literature; their inherent quality is a spontaneous formation out of the inner soul of this great creator.

These thoughts about the genius of French occurred to me because it seemed to me that there was a great analogy in this respect between French and Bengali. Certainly it would not be quite correct to say that the evolution of the Bengali language was slow and steady like that of French. At least one upheaval, a revolution, has taken place on its coming into contact with Europe; under its influence our language and literature have taken a turn that is almost an about-turn. But this revolution was not caused by a single person,—not even perhaps Bankim. Dante and Homer are the creators, originators or the peerless presiding deities of Italian and Greek respectively, just as Shakespeare may be said to have led the English language across the border. But if to anybody it is to Tagore that a similar place can be assigned. He made Bengali transcend its insular circle. As Tolstoy made the Russian language join hands with the wide world or as Virgil and Goethe imparted a fresh life and bloom, a fuller awakening of the soul of poetry, to Latin and to German, so too is Tagore the paramount and versatile poetic genius of Bengal. I think that Tagore has in many ways the title and position of a Racine amongst us. There is a special quality, a music and rhythm, a fine sensibility of the inner soul. The uniqueness is in the heart; a sweet ecstasy, an intoxicating magic which Chandidas was the first to bring out in its poignant purity and which has been nourished by Bankim, has attained the full manifestation of maturity, variety, intensity and perfection in Rabindranath. Here too an aspect of supreme elegance is found. Bengali, like French, has a natural ease of flow. Madhusudan took up another line and sought to bring in an austere and masculine element—à la Corneille. Some among the modern writers are endeavouring to revive that line and naturalise it; even then the soft elegance, the lyric grace so natural to the language has attained almost its acme in Tagore. To be sure, among us Tagore is the One without a second.

RABINDRANATH, TRAVELLER OF THE INFINITE PART 1

In Rabindranath, in his life as well as in his art,—especially in his poetry—the thing that has taken shape is what we call aspiration—an upward urge and longing of the inner soul. In common parlance it is a seeking for the Divine, in philosophical terms it is a spiritual quest. But Rabindranath is a poet, and he is a modern poet. He cannot be wholly included in the older category, fixed in a mould of clear definition. To be sure, the special characteristic of his consciousness is to keep as far as possible the aim, the ideal, the goal and the Deity of the worship undivided and inexplicable. To make something definite and clear is to limit and make it gross and material. Therefore to name the Deity whom he loves, adores and worships he has used words that are expansive, general and vague—infinite, boundless, formless and non-manifest. If the Deity appears in a manifested form the worship of the worshipper ends. The Deity also will no longer be a Deity of the worship. But it does not mean that the Deity of Rabindranath is ‘the One beyond sound, touch, form and change’ of the Upanishad. His aspiration is for another realisation of the Upanishad:

“One who has taken this form, that form and all the forms.”

Or:

“He being bodiless dwells in the forms and non-forms as well.”

That supreme truth cannot be called formless simply because it has no special form. He is formless since His form has no limit. He is not exclusively bound by any special form. He is not merely infinite and boundless but also delightful and ambrosial. He is endearing and with His endearing form He dwells behind all forms. It cannot be said definitely whether He is seen or not through forms—in this way He attracts the soul of man perpetually towards Him.

Rabindranath has not seen his Beloved with his eyes open. He has not sensed Him with unblinking eyes, nor even has he wished to do so. His delight and achievement consist in making Him mysterious and nebulous by keeping Him aloof, and veiling Him in innumerable names, forms, colours, rhythms, hints, gestures, ways and means. That object is infinite and boundless; it is more so, because it is unknown and unfamiliar or almost so

Far yet near,

Near yet far.

So it is, as it were, a damsel unfamiliar, remote and fond of mirth and play. It is a constant separation from the Beloved—though it is an object of deep love—that has made this love intense, sweet and poignant, moving and overflowing. Such a longing for the far-off Beloved made Shelley restless. His ‘Skylark’ is the living idol of this longing. Shelley’s object of love also is a Deity dwelling in a distant world:

The desire of the moth for the Star,

Of the night for the morrow,

The devotion to something afar—

From the sphere of our sorrow.

This is equally the quintessence of Tagore’s message. For this reason people brought up in European culture used to call Rabindranath the Shelley of Bengal. There is a close kinship between the two in this upward urge.

This spiritual aspiration was called quest in the scriptures of the West. The quest of the Knights for the Holy Grail inflamed the heart of Europe to a great extent for a time. Its art and literature bear abundant indication of this. I bring in the West here, for the poetic consciousness of Rabindranath is no less full of the West than of the Upanishads. In many cases we see that as the Vedanta is in his inner Being, in the marrow of his bones, so there is Europe in his poetic consciousness, in flesh and blood. Rabindranath is a unique blending of these two.

However, due to the unique quality of the aspiration, curiosity and seeking which we have mentioned as being in his heart, two qualities are perceptible in his poetical style. First, the style, the speed, the swing of rhyme and rhythm and the cadence of tune. Starting from ‘Nirjharer Swapna Bhanga’, the awakening of the fountain, ‘My heart dances to-day’, and ‘Lo, he comes, he comes with rapture’, to ‘the restless, irresistible flutterings of the wings’, of ‘Balaka’, the same style shows itself in a fast and almost merry stepping. A restlessness for an uninterrupted forward march of the soul and the inner consciousness to proceed ever still more, still further, still higher is the nature of the divine flame residing in the heart. So the delight of journeying incessantly, without a halt anywhere in any shelter, journeying for the sake of journeying—this becomes the aim and ideal of man’s life. The Vedic Mantra—‘Charaibeti’, ‘move, move on’—was therefore so dear to Tagore. Is there such a thing as a definite and fixed ideal? We surpass the aim of today and another appears on the horizon. Today’s high precipice is left behind as a foothill. A higher precipice looms ahead, and behind it rears one still higher, thus an unending range. There is no stopping, never say there is ‘no further’.

The message of the poet’s heart runs:

To every one Thou hast given a home,

Me only the road to press on.

Or:

O there is no home for you,

No bed of flowers,

Only two wings and the vast courtyard

Of the sky.

• • •

O Soul, O Bird of my heart!

Close not, O blind one, your wings.

Further:

O Charioteer of my life’s journey!

I am a pilgrim on the eternal road,

I bow to Thee on my wayfaring.

This sense of ever progressive movement is very evident in Rabindranath. Several critics have compared Bergson with him in this connection. There is much similarity between the two; but, I think, their difference also is vital and fundamental. The progression of Bergson is the final, ultimate, sole and primeval truth. It is mere progressiveness without any cause. It is doubtful if it has any other quality. A line of evolution may be noticed there but that is a secondary sign of this progression. There is no purpose behind it. If there be any, then this movement loses its natural, spontaneous rhythm. But Tagore is a child of the Orient. However enamoured he might be of progressiveness, there is somewhere behind him “the static poise in home” of the Upanishads. However great might be his advance for the sake of advance, he knows after all that there is:

Peace boundless where comes a mighty halt…

Quiet, sublime, deep and silent Glory.

The movement in Rabindranath is not for itself, neither aimless nor eyeless. It is open to the light, it is luminous.

Each star of the sky invites the human soul.

The invitation to him is from all the worlds,

To the horizon of the East in teeming light.

Again,

Let thy deathless flower bloom towards the light

In the world and the worlds beyond, ever anew.

We have said that this movement is fundamentally a spiritual aspiration, a longing for the Divine—this aspiration and this longing are sweet, deep and penetrating and at once refined and transparent. The élan vital of Bergson is mainly a movement of nature and the life-force, however he might have tried to put on it towards the end a veneer of spirituality, of Christian religiosity.

Indeed this dynamism has given a unique stamp to Tagore’s mode of expression. The peace and silence about which he speaks often dwell in the consciousness hidden at the core as a refuge or as a hope and anticipation, an intimation from beyond—even as there is a pause in the heart of rhythm or at the end of a bar of tune there is a stillness. Cadence in Tagore represents the movement of progression in life and consciousness. The natural echo of time-flow and sound and melody and motion we find in the following lines:

Whoever moves goes on singing

To the land of abundance.

Or,

Farther and farther

The road goes on ringing with a thin, poignant,

Lengthening note.

Dance and music almost run abreast. From the viewpoint of spiritual realisation we find that aspiration and invocation have the same origin. The spontaneous utterance of the heart is but the mounting self-revelation and self-declaration of the aspiration.

All that I have not attained,

All that I have not struck

Are vibrating on the chords

Of thy Lyre.

Let us recollect in this connection Shelley’s

And singing still dost soar and soaring ever singest.

Tagore is known to us as music incarnate. The simple, natural form of his poetic soul has expressed itself through songs and lyrics. Let us now deal with the second quality that derives from a free, unbarred movement and proceeds towards the indefinable at its best. According to many a critic it is a great flaw. To some it means nothing but ambiguity, while to others it is, to say the least, lack of objectivity. Let us examine it. Listen, for example,

The teeming clouds rumble

With heavy showers.

Alone I sit on the rim of the rill

Empty of hope.

Sheaves of sickled paddy are collected in heaps;

The fleeting current of the river, full to the brim,

Is chill to the touch.

Rains interrupt the harvest-work.

‘Sonar Tari’

Our mind and heart are carried away by the seductive charm of beautiful language, fine rhythm and an enchanting picture. But our physical eyes fail to seize a meaningful substance or a direct and clear experience behind the words. No doubt, evidently there is an effort to formulate some realisation, but nothing solid has been achieved. Everything is fluid and thin and tenuous, about to vanish like vapour. That is why critics of the classical school accused Tagore of obscurity and enigmatic vagueness—all a play of whims, caprices and fancies—the clear, direct and positive certainty of the truth-seer is lacking there—Rabindranath cannot sing in unison with the Vedic sages, “Jyok cha Suryan drishe"—“May we behold the Sun with open and undazed eyes.”

To some extent, perhaps, it is true that if we compare Tagore with those who stand on the peaks in world literature we find in their creation an utmost, flawless harmony and synthesis between speech and substance, while in Tagore we find on the whole speech carrying more weight than substance and this is why his poetic genius, as it were, somewhat falls short of perfect perfection—except in a few instances. But that, it may be answered, would be demanding something from Tagore which is not germane to his nature and genius; it would be, as it were, to measure him by a standard different from his own. To be sure, substance does not mean mere wealth of clear intellectual thoughts or solidity of subject matter. Substance means the real essence, the very core, the thing in itself, a delight-truth gleaned in consciousness, made vibrant with life. And it may be said that even this is the law of a particular formula of creation—but Rabindranath has followed another law. We may take here an example. As a sculptor Michael Angelo had no parallel among the artists. One special trait of his carving was this that he hardly ever completed a figure to a final finish; he left it unfinished to a certain extent; the unfinished portion in its rawness was suggestive of things unsaid. Probably he would indicate in this way that the statue as a statue has not an independent value of its own but is part of nature’s own beauty around a statue—it was not a model according to the Greek ideal—a creation flawless, exquisite and perfect in every feature, complete and sufficient in itself—but quite separate from other creations. In our country the practice of carving out some portion of a whole hill and shaping out of it some idol or cave temple was in vogue. The inner sense of that practice was perhaps to prove the unity and indivisibility of art and nature and how they harmonise and commune with each other. A similar excuse may be put forward on behalf of Tagore. A lightness and sinuosity, turns and returns in the movement, weave out the essential theme, because of the pressure, the necessity, the very law of the consciousness. And that also has characterised the impetus of the upward drive of aspiration—a thirst for attaining a farther and farther progression—the ever burning and increasing flame of the psychic Being, the everspreading rays of the immortal light. This unending, ceaseless, free and absolute aspiration, this voyage to the Unknown—

Behold

The boundless main in the West,

The flickering light like hope

Quivers in the water—

Or,

Not here, elsewhere, elsewhere, in some other clime.

The poet did not put a limit to his quest—the uniqueness of his own nature implanted itself perceptible and living in his style and manner. Realisation signifies union; the poet was not after union—but the yearning for union:

Where is light, O where is light!

Kindle it with the fire of separation.

Saint Augustine in one of his sayings describes the state in which he did not love but loved to love. The heart of Tagore was dyed with something of this holy Augustinian tint.

RABINDRANATH, TRAVELLER OF THE INFINITE PART 2

It is an interesting study how the upward urge of aspiration, the basic note of consciousness runs like a golden thread through all different modes and manners and reveals itself under various names and forms. To begin from the beginning with ‘The Awakening of the Fountain’:

I shall rush from peak to peak,

I shall sweep from mount to mount,

With peals of laughter and songs of murmur

I shall clap to tune and rhythm.

Here is the first awakening of aspiration—the poet is still in his early youth, full of fun and frolic, laughter and dance, and looking outward and given to outer things.

Let us next come to the ‘Golden Boat’. It presents another mood, another state:

Who comes singing to the shore as he rows?

It seems to be an old familiar face.

He moves with full sail on;

Looks neither right nor left.

The helpless waves break on either side.

It seems to be an old familiar face.

Consciousness is turned inward; the first fervour of aspiration, at once sweet, intense, full of pathos, has struck the chords of life. No loud demonstrations, there is a profound and touching cadence, the sharp call of a one-stringed lyre—a condensed realisation, the gait easy and rhythmic in its simple sincerity. Side by side there woke up a curiosity and an enquiry that made the mystery of life more mysterious, more delightful.

Further on we hear in ‘The Philosopher’s Stone’:

The long way of the past lies lifeless behind.

How far from here the end cannot be measured.

From horizon to horizon

It is all the glistening sands of the desert.

The whole region is dimmed by the oncoming night.

According to the Christian saints this state is the ‘dark night of the soul’. They say, the familiar past has been left behind, the new life has not been achieved—the foretaste of it has slipped away, there is no return to the past, the path to the new life is not known—a helpless anxiety surges up. But the night of our poet is by no means as dark as that of the Christian saints. The journey towards the unknown destination has almost the same aspect as a description of the dark night usually gives us, but in the midst of this darkness glitters the noiseless laughter of that ‘feminine absconder’; the poet is able to say even when engulfed in that night:

Only the sweet scent of thy body is wafted by the wind,

Thy hair driven by the wind is scattered on my bare body—

Rabindranath’s pain did never become extreme or tragic, the note of union is there hidden in his pang of separation: “O Death, thou art an equivalent to my Lord Krishna.” Death is not death pure and simple; immortality lies hidden therein. The poet had always a clue to the One in whose pursuit he was ever vigilant. In his ‘Urvasi’ this urge has reached its acme. It is there that his insight has fully opened up. The poet has attuned all the strings of his life-energy to the highest note of his inner consciousness. The realisation is as profound as the language is gathered and condensed, the metre and rhythm too are of the finest and richest quality. Here at least once the glory of a real Epic has shown itself in his poetry. The full-throated Epic tune is sounded in the voice of the poet:

O Urvasi swaying soft and sweet,

When thou dancest before the assembly of the gods,

Thrills of delight course through thy limbs,

Waves upon waves swirl rhythmically in the bosom of the ocean,

The undulating tips of the shivering corn

Appear like the fluttering skirt of mother earth.

From the necklace hung upon thy breast

Drop down the stars on the floor of the sky.

And all at once man loses his masculine heart in sheer rapture.

The blood flows leaping and gurgling,

In the twinkling of an eye thy girdle gives way

At the far horizon, O naked Beauty!

In the next phase, in his middle age when the poet arrived at a mature consciousness, when he wrote his ‘Ferry Boat’, he seems to have come down to a more normal, ordinary and homely tune in his expression, suited to the movements of every-day life. Superabundance of robes and ornaments has fallen away; what is normal, common, commonplace—not the pomp of vernal lush but merely the sobriety of autumn—is now enough; the aspiration of these mellow days resembles the sweet, pastoral tune of the religious mendicant’s one-stringed lyre.

From the golden beach of the other shore

Imbedded in darkness

What enchantment came with a song upsetting my work?

This tune has been uppermost in most of the poems of ‘Gitanjali’ and ‘Gitali’. Afterwards we hear once again the resonance of a high emotional, impassioned voice. The tune reaches a lofty pitch, the melody is far-flung, but it is more steady and firm; no longer something fluid and amorphous but a formulation in solid concepts, an upsurge from a deeper and self-possessed source—I am referring to ‘Balaka’:

I hear the wild restless flutterings of wings

In the depth of silence, in the air, on land and sea.

Herbs and shrubs flap their wings over the earthly sky.

Who can say, what is there in the tenebrous womb of the earth?

Millions of seeds open out their wings

Even like flights of cranes.

I see ranges of those hillocks, those forests

Moving with outspread wings from isle to isle,

From the unknown to the unknown.

With the flutter of starry wings

Darkness glimmers in the weeping light.

Tagore, as it appears to me, never again reached such heights of bold imageries and in such an amplitude of melody. Enchanting moods and manners, figures and symbols, diverse and varied, were there, every one of them with its own speciality, beauty and gracefulness but it is doubtful whether they possess the sense of vastness and loftiness and epic sweep and grandeur to that extent as here. The urge, the movement that finds expression here is not concerned merely with the aspiration of human beings or individuals—here is expressed in a profound, grandiose voice the aspiration of the inert soil and the mute earth—not merely in conscious beings but also in the subconscient world there vibrates an intense, passionate, vast, upward longing. A sleepless march proceeds towards the light from the bottom of the entire creation—not only it is finely and adequately expressed but that reality has assumed its own form as it were in word and rhythm, as a living embodiment. In ‘The Awakening of the Fountain’ we notice the lisping of this grand message, although the fountain is a mere symbol or an example, a mere support there, and the significance is also to a considerable extent of the nature of an oration or discourse, nevertheless fundamentally the poet’s dream remains the same. So, we can say, what commenced with the ‘Fountain’, the cry of a chord, the invocation of a single limb, has become a full-fledged orchestral symphony in ‘Balaka’—the wheel has come full circle.

RABINDRANATH THE ARTIST PART 1

To-day we just want to study Rabindranath the man and not the poet Rabindranath. The poet may raise a slight objection—he may say that if we want truly to evaluate him we must consider him as a poet. What he has done or not done as a man is insignificant; he has stored up in his poetry whatever eternal and everlasting was there in him, in his true being and real nature. The rest is of no real significance or value. In that respect he may not have a good deal of difference from others, any marked speciality. The greatest recognition of a poet lies in his poetical works. To give prominence to his other qualities is to misunderstand and belittle him.

But in dealing with Rabindranath the man we are not going to concern ourselves with his worldly and household life. We are going to study the real man in him whose one aspect has manifested in the poet Rabindranath. Perhaps that real man may have had his best and greatest manifestation in his poetry; still the truth, the realisation, the achievement of the inner soul that wanted to reveal themselves through that manifestation are our topic.

Beauty is the chief and essential thing in the poetic creation of Rabindranath. He appreciates beauty and makes others do the same in a delightful manner. He has made his poetical work the embodiment of all beauties culled from all places little by little, whether in the domain of nature or in the inner soul, or in body, mind and speech. Beautiful is his diction. Mellowness of word and the gliding rhythm have perhaps reached their acme. Charming is his imagination. Varied and fascinating are the richness and intricacy of thought and the fineness and delicacy of feeling. The themes of his narratives are attractive in themselves. He has made them more beautiful and decorative by clothing them in the most graceful words of subtle significance.

The mango buds fall in showers,

The cuckoo sings.

Intoxicated is the night,

Drunk with moonlight.

“Who are you that come to me,

O merciful one?”

Asks the woman.

The mendicant replies:

“O Vasavadutta, the time is ripe

To-night; so to you I come.”

Or,

The stars drop in the lap of the sky

From the chain hanging down to your breast.

The heart is overwhelmed with ecstasy

In the core of Man’s being:

Blood runs riot in his veins.

Suddenly your girdles give way

On the horizon, O naked beauty!

What a visionary world of matchless and unique beauty is unveiled before the mind’s eye! That is the true Rabindranath, the creator of such magic wonders. Perfect perfection of beauty is inherent in the nature of his psychic being. The advance he has made in respect of knowledge and power has been far exceeded by that of beauty. Knowledge and power have a subordinate place in his consciousness. They have been the obedient servitors of beauty. Rabindranath’s soul seems to have descended from the world of the Gandharvas, who are the divine Masters of music. This Gandharva saw the light of day to express and spread something of real beauty in the earthly life. His mission and performance were to manifest beauty in all possible ways. Many have contributed to the creation of beauty in poetry and there are works which are supreme in poetic beauty. There is no doubt that Tagore is one of the foremost among them. But the especiality of Rabindranath lies in the fact that the poet in his inner soul permeated his whole being. Even if he had not written any poetry his life itself would have been a living work of beauty. He himself was handsome in person. Sweet was his speech. Attractive was his decorous demeanour. Beauty was stamped on his inner nature and outer activities. He was all along creating beauty around him and proceeding from beauty through higher beauties towards the supreme Beauty.

It has been already said that Rabindranath’s inner Being was a creator of beauty. But this beauty he has expressed more through the vibrations of rhythm than through the cut of form. We notice that the greater stress of his fine art has been laid on movement than on static beauty and more on the gesture of limbs than on their limned outline. We find that his poetic creation has been more akin to the art of music and of the dance than that of sculpture and architecture. He has attained to sheer beauty through movement and not through immobility, not so much through sight as through sound. The poet eagerly wants to listen to and seize upon the tunes of rhythms that overflow in a silent urge behind the external forms or structures, the life-vibrations that have manifested in the creation echoing with sounds. The poet wants to bring out the suggestiveness behind the significance of words, the incorporeal import comprised in the sentence otherwise framed in ordinary words.

The poet says:

His Face my eyes have not met,

Nor have I heard his Voice.

At each hush do I hear

The sound of his footsteps.

Further:

He who is beyond the flight of mind,

His Feet through my songs

Do I barely touch,

But myself I lose in the ecstasy of melody.

We note that even where he has given a definite form to beauty he has not put it forward as a fixed point of concentration. He has set forth beauty in its moving liquid form. For example—

The showers come rushing to the fore,

The tender paddy plants move to and fro

With no respite.

The dance, the rhythmic movement have given whatever form beauty has. On the whole we can describe the goddess of poetry of Kalidasa as standing, in his own words, ‘immobile like a movement depicted on a picture’, but in the creation of Rabindranath we see that ‘the singing nymph passes by breaking the trance—.’

In every turn of all these varied forms of cadence and vibration there is an ecstasy, the dying curve of a soft tune that gathers in its fall all the sweetnesses that the movement was carrying—the whole merging as it were into a sea of rich peace and silence. The poet’s eloquence is most intimately married to his silence. On one side, his vital being, athirst for delight, is overwhelmed with the mass of Nature’s wealth, luxuriant in colours and smells, in peals of laughter and rhythms of dance; his senses enamoured of beauty are eagerly prone to hug the richness of external things; he wants to seize upon the Self, God, through the embrace of the senses and the fivefold life-force. Still, there is the other side where through all these varied vicissitudes his aim finally settles in “the vast peace that lies in the core of peacelessness.”

In the midst of his play with the world of action and commotion in which gross words play about loudly and ruthlessly, often he leaves them behind and in his ideas and suggestions he climbs up to a subtler plane where the rhythm, the tune, not the vocable comes to the forefront. The music, the pure music fills up the background and is not overwhelmed by the concatenation of words and phrases that lead perhaps to a physical preciseness but also to a certain grossness. That music has in it a purity, serenity, lightness, sweetness and beauty that uttered syllables have not.

For, there

Unheard voices innumerable

Exchange their whispers in the void.

In their silent clamour

Unformed thoughts move forward

Band by band.

So the aspiration of the poet is:

I would go with the lyre

Of my life to the One

In whose measureless halls

Songs not audible to the ear

Are sung eternally.

There is something here like what the ancient Greeks used to call the music of the spheres.

We discover almost the primal urge of beauty and the fount of rhythm. It seems we are at the point when the creation began to assume forms at the first vibrations of life—all proceed from the vibrant life—Sarvam pranam ejati nihsritam—this mantra of the Upanishad was very dear to Rabindranath and he cited it very often. Rabindranath was a worshipper of Brahman, but more of the Brahman as the primal sound, the original wave, the vibrating note that is to manifest in creation. And the unique success he attained in the cult of this Deity of his heart is the speciality and glory of his poetical creation. In the following mantra Rabindranath depicts the image of his Deity in trance:

The note has ceased

But it would linger still ceaselessly,

The lute plays on although in silence,

Although without necessity.

RABINDRANATH THE ARTIST PART 2

There is an inner discipline for the attainment of Truth and Good. Truth and Good were the objects of sadhana to Rabindranath from the aspect of their beauty and grace. He did not worship them so much for their own sake as because the real Truth and Good are really and supremely beautiful. And they attracted him only because of their beauty.

Love is a main theme of his poetry and he is a loving personality. In the terms of the Vaishnava sadhaka he is a graceful personality, ‘Supurusha’. But his love too is the quintessence of beauty. So his love speaks to him:

You have taken me by the hand to the Elysian garden of bloom,

the abode of immortality—to shine in my eternal youth there,

like the Gods.

Limitless is my beauty there.

Rabindranath did not enjoy love for its own sake as did Chandidasa. Beauty has found its highest revelation and acme in love. So he had to become a lover. The ultra-modern experience has separated love from beauty, rather it is trying to bring about a union with ugliness. In that sense Rabindranath is very ancient, treading the Eternal Path.

The beauty depicted by Rabindranath consists in harmony, synthesis, uniformity, contentment, serenity and tranquillity. Wherever there is conflict, roughness, crudity, harshness, there no beauty is found, there a rhythm is broken, the flow is hampered, the tune is disturbed, there is some flaw in the movement. It is why Rabindranath’s God is supremely beautiful, loving and graceful. And

The entire abode is flooded with the charm of His face.

Therefore the daily prayer to his Beloved is also:

Make me pure, bright and beautiful,

O my Lord!

And

Let all things beautiful in life resound to the melody of music.

God is God because He is the golden thread running through all things of the universe.

All are unified in your consciousness wide awake.

Rabindranath’s philanthropy or altruism is the outcome of this union; it is brought about by the attraction of the beauty of this union. The whole creation is adorable, a desired prize. “We live and move and have our being in the effulgent delight of the ether.” For a supremely sweet harmony pervades the creation. Rabindranath’s ideal of the vast human collectivity has also been inspired by this sense of harmony. All the nations, all the countries of the world, keeping still their speciality and distinction, will stand united with one another—the human society will thus attain to a flawless beauty. The rivalry among equals, the tyranny of the superior over the inferior; again, the slave-mentality of the low before the high—all such abject habits must be renounced, because they are harsh, ugly and devoid of beauty. Peace, love, generosity and friendship can make men beautiful individually and collectively.

At the root of Rabindranath’s patriotism also there lies the same love for beauty. The lack of beauty in slavery tortured him more than anything else. The ugliness of poverty was more unbearable to him than the actual physical destitution. If he could have viewed the wants of life at their own value like Mahatma Gandhi then he would have at least once plied the spinning wheel. But to him ease or affluence by itself has no importance. Affluence would have its real value if it contributed to the rhythm of life. That is why his patriotism laid a greater stress on construction than on destruction. To settle things amicably, instead of attacking the enemy, instead of wrangling with the foreigners, to put one’s own house in order, to repair and beautify was considered by him a real work to be done. To build is to create. To create is to fashion a thing beautifully. The ideal of his patriotic society has to foster all limbs of the collective life of the entire nation, to make it a united organism, to endow it with the beauty of forms and rhythm in action.

So we say that the beautiful poetry and the poetry of beauty written by him are even surpassed by the beauty that he brought down into our life; particularly in the life of Bengal. The whole contribution of Rabindranath is not exhausted by his poetical works. Firstly, his was the inspiration that formed around him a world of fine arts, a new current of poetry, painting, music, dance and theatre. Secondly, his was the life-energy whose vibration created in our country a refined taste and a capacity for subtle experience. Through his influence a consciousness has awakened towards appreciation of beauty. Thirdly, the thing which is, in a way, of greater value is this that if there has been a gradual manifestation of order and beauty in our ordinary daily life, in dress and decoration, in our conversation and conduct, at home and in assemblies, in articles of beauty and their use, then, at the root of it all, directly or indirectly the personality of Rabindranath was undoubtedly at work. Among Indians, the Bengalis are supposed to have particularly acquired a capacity for appreciation of beauty. That this acquisition has been largely due to the contribution of the Tagore family can by no means be denied. We do not know how we fared in this respect in the past. Perhaps our sense of beauty was concerned with the movements of the heart or at most with material objects of art. Perhaps, we had never been the worshippers of beauty in the outer life like the Japanese. Yet whatever little we had of that wealth of perfection within or without had died away for some reason or other. The want of vitality, the spirit of renunciation, poverty, despair, sloth, an immensely careless and extreme indiscipline made our life ugly. At length the influence that had especially manifested around Rabindranath came to our rescue and opened a new channel to create beauty.

Why should we speak of our own country alone, why should we try to keep his influence confined to Bengal or India only? I believe Europe, the West, have honoured him so much not primarily for his poetry. The modern world, freed from its life devoid of beauty, due to the unavoidable necessity of technology and machinery of utility and efficiency, was eager at last to follow in the footsteps of Rabindranath to enter into an abode of peace and beauty, a garden of Eden.

THE LANGUAGE OF RABINDRANATH

If Bengali has become a world language transcending its form of a provincial sub-tongue, then at the root of it there is Rabindranath. To-day its richness has become so common and natural that we cannot conceive immediately that it was not so before Tagore’s mighty and ceaseless creation worked at it for half a century. I am not speaking of the literature, I am speaking only of the richness of the vocabulary, the diversity of the speech form, its modes and rhythms. The capacity of a language lies in its power of expression: that is to say, how many subjects can it express itself on and how appropriately? In the gradual progression of the Bengali language Bankim Chandra was one of the main and foremost stepping-stones. But in Bankim’s time Bengali was only in its adolescence—at best, its early youth—its formation and movement were rather narrow, experimental and prone to uncertainty. In Rabindranath we find it in its full-blossoming, mature capacity, definiteness and diversified genius. The growth and spread of Bengali has not reached its culmination, the process is still in full swing. And I need not dwell here upon its still more advanced stage and maturity in the future. Up to Bankim’s time, the modern and therefore somewhat European way of thought and expression did not come naturally to Bengali—it became difficult, laboured, artificial: e.g., ‘An enquiry into the relation between other phenomena and human nature’ of Akshay Kumar Dutta or even ‘Bodhodaya’ of Ishwar Chandra. It was Bankim Chandra who was the pioneer in whose hand this line of development attained something like an ease and naturalness of manner. Even then it was no better than a beginning. But to-day Bengali possesses the capacity to express easily and adequately any literature from Greenland to Zululand, from the most ancient Egypt and Babylon down to modern Europe and America. The goddess of speech who inspired Tagore is a maker of miracles. It was Tagore who, it might be said, all by himself worked this mighty change and transformation.

Directly—and more indirectly, that is to say, through an impalpable influence—it was his personality that lay behind this achievement.

Should a catalogue be ever made of the new words coined by Rabindranath, it would be a very instructive lesson. Numerous are the words—old words found only in the dictionary—that he has made current coin. In the same way innumerable are the words—used one time colloquially or in a regional dialect—that Rabindranath has elevated to the level of literary distinction. Moreover, he had a special genius in coining words and that expressed a characteristic trait of his creative genius. Primarily, his words seem to spring from the heart, from the élan vital, natural to the Bengali consciousness. There were two rocks on his way to linguistic transformation. And he beautifully escaped and eluded them both. On the one hand, there is no heaviness in him, none of the massiveness of correct and flawless words composed by pedants and grammarians. On the other hand, there is no grotesqueness, nothing of what personal whim and fancy and idiosyncrasy engender. If his words in their structure break certain strict rules and regulations, they yet are quite in tune with the inner nature and form of the language; if free, they are still natural. Secondly, the grace and beauty of the words raise no question. A word, in order to fulfil its role, must have an easy and inherent power of expression—it must be living and full of vitality. Still more it must be sweet and beautiful. In the lexicography of Tagore all these qualities are in abundance. Moreover, in his language there is nothing squalid, lifeless, heavy, feeble, harsh and jarring to the ear; indeed, his language is perfectly graceful, beautiful and nonpareil from all sides—

“Graceful, more graceful, the most beautiful surpassing all beautiful things.”

Tagore’s Goddess of speech is a pinnacled exquisiteness of beauty, harmony, balance and skill. Bankim’s language also is beautiful and graceful—it is not rough and masculine; it is also charming but there is not in it such profusion, intensity and almost exclusiveness of grace, sweetness, beauty and tenderness as are found in Rabindranath. Prodigality, luxuriance and even complexity are hall-marks of Tagore’s style. Bankim’s is more simple and straight and transparent, less decorating and ambulating. There is in Bankim what is called decorum, restraint, stability and clarity, qualities of the classics; he reminds us of the French language—the French of Racine and Voltaire. In Rabindranath’s nature and atmosphere we find the blossoming heart of the Romantics. That is why the manner of his expression is not so much simple and straight as it is skilful and ornamental. There is less of transparency than the play of hues. Eloquence overweighs reticence. Echoes and pitches of many kinds of different thoughts, sentiments and emotions intermingle—his language moves on spreading all around, sparkling at every step. Subtlety of suggestion, irony and obliquity, a lilting grace of movement carry us over, almost without our knowing it, to the threshold of some other world. Rabindranath’s style is neither formed nor regulated by the laws and patterns of reason, the arguments and counter-arguments of logic. It is an inherent discernment, the choice of a deep and aspiring idealism, the poignant power of an intuition welling out of a sensitive heart, that have given form and pace to his language. Reason or argument in itself finds no room here. That is only an indirect support of a direct feeling, a throb in vitality. This language has no love, no need for set rules, for a prescribed technique, so that it may attain to a tranquil and peaceful gait. It has need of emotion, impetus and sharpness. It is like the free stepping of a lightning flare, an Urvasie dancing in Tagore’s hall of music.

But it does not mean that this language is overflowing with mere emotion. Here too there is a regulated order and restraint. The final growth and perfection of a language has something of the rhythm of an athlete’s body in movement—in the steadied measure of the strides of a sprinter, for example. The transparency of intelligence as reflected in the classical manner, the firmness and fixity delivered by reason, the simplicity of syllogistic orderliness are not to be found here. But in our poet’s creation, even in his prose the logic of intelligence may not be evident but there is a logic of feeling which is still cogent and convincing, yet more living and dynamic.

As regards the third creator of Bengali literature, I mean Saratchandra, we may notice here the difference between him, and Tagore. The language of Saratchandra is as straight, translucent and simple as that of Bankim; but Bankim was not always averse to decoration and embellishment, whereas Saratchandra was wholly without any ornamentation. But the pressure of reason and rationality is not the cause of Saratchandra’s simplicity. It is because he has shaped his language to suit the common thought, the available feeling, a natural life. But he has polished it in his own way and made it extremely bright, often scintillating. With all its clarity and directness Bankim’s language is for the cultured mind—urban or metropolitan, Saratchandra’s manner can be called rural. It will be wrong to call it vulgar, even in the Latin sense (plebeian or popular), that is, commonplace—or a language of the country-side. The similarity between Saratchandra and Tagore is that both are progressive, rather very progressive; speedy, rather very speedy, but there is a dissimilarity in the manner of their progressiveness and speed. Tagore’s Muse moves speedily but in a zigzag way, observing all sides, throwing out various judgments and opinions, scattering flashes of a curious mother wit. Here are all the playful lines of a baroque painting at its best. Saratchandra goes straight to his goal—as straight as it is possible for a romantic soul to be. He allows himself, we may say, a curvilinear path, as that of an arrow heading direct towards its goal. There is a vibration lent to it by the drive of a subtle Damascus blade. It is flexible and yet firm. The flow of Tagore can be compared to that of a fountain—it is rich in sounds and hues. Saratchandra’s is the light-pinioned bird that flies in the sky in silence. We find in Bankim a wide calm, happiness, clarity and beauty. In Tagore it is a tapestry woven by the free outpourings of the mind and the heart. In Saratchandra it is the dynamic simplicity of a vitality meaning business.

I spoke of Rabindranath’s ornamentation. But we must bear in mind that this ornament is not a material one. Not in the least heavy, loaded, luxurious like that which an old-world beauty carried on her limbs; it is as light as the jewellery which a belle puts on to-day. The tapestry of myriad forms has been wrought in gold threads, made thin and fine and almost tenuous and yet firmly holding together. This embroidery is the beautiful itself, for it is a work subtle and refined and meant to be beautiful. It is a beauty requiring no outer grandeur, no wrought-out gold and satin of volubility and rhetoric. It bears in its own limbs, as it were, the glow of an inherent grace and charm.

To-day the Bengali language is eager and zealous to go forward for an ever new creation. It is quite natural that it may go astray at times in the hands of many of its adorers. In this connection it is good to bear in mind and to keep to the fore the example of Rabindranath as a supreme exemplar even if one does not want to follow or imitate him. Rabindranath himself has also created many new things from his aristocratic pedestal, even he came down and attempted the ultra-modern style. But his speciality and power lie here that he has never transgressed the limit of the beautiful and the appropriate. Besides, wherever or however far he might have ranged, he has given beauty its supreme place. In following the new and modern style he has founded everywhere beauty and bloom and fulfilment. He laid bare his inner soul.

RABINDRANATH TAGORE AND MODERNISM PART 1

Bengali literature has reached the stage of modernism and even ultra-modernism. This achievement is, we may say point-blank, the contribution of Rabindranath. Not that the movement was totally absent before the advent of Rabindranath. But it is from him that the current has received the high impetus and overflooded the mind and the vital being of the Bengali race. We can recall here the two great artists who commenced modernism—Madhusudan and Bankim. But in their outlook there was still a trace of the past, in their ideas and expressions there was an imprint of the past. The transition from Ishwar Gupta and Dinabandhu to Bankim and Madhusudan—not from the viewpoint of time but from that of quality—is indeed a revolution. Within a short span of years the Bengali way of thinking and the refinement of their taste have taken a right-about turn. It was Bankim and Madhusudan who have placed Bengali literature on the macadamised road of modernism. Still, while walking on that road, somehow we were not able to shake off completely the touch of clay under the feet and the smell of swampy lands around. It was Tagore’s mastercraft that enabled Bengali literature to drive in coach-and-four through the highways. Not only so, in addition he has enriched and developed it to such an extent that we feel, pursuing the image, as if we could safely drive there the motor car or even the railway train.

The term modern, no doubt, relates to the present time, but there is in it a factor of space as well. It is the close communion among the different countries of the world that has made modernism modern. The relation of give-and-take among many and various countries and races has given each country a new atmosphere and a new character. The newness that has thus developed is perhaps the fundamental feature of modernism. Bankim and Madhusudan were modern, for they had infused the European manner into the artistic consciousness of Bengal. Europe itself is indeed the hallowed place, the place for pilgrimage of our epoch. Humanity in the modern age plays its great role in Europe. So to come into contact with Europe is to become modern—to take one’s seat at the forefront in the theatre of the world. Thus it is that Japan has become modern in Asia. And China lagged behind for want of this contact. In India it was the Bengalis who first of all surpassed all others in adopting European ways. That is why their success and credit have no parallel in India. From Bharatchandra, Ishwar Gupta even up to Dinabandhu the genius of Bengal was chiefly and fundamentally Bengal’s own. The imagination, experience and consciousness of the Bengalis had been until then confined to the narrow peculiarities of the Bengali race. Bankim and Madhusudan broke the barrier of provincialism and cast aside all parochialism and narrowness of Bengalihood and brought in the imagination, consciousness, manners and customs of other lands.

Rabindranath too has done the same, but in a subtler, deeper and wider way. Firstly, at the dawn of modernism, the two currents, foreign and indigenous, though side by side did not get quite fused. They stood somewhat apart though contiguous. There was a gulf between—a difference, even a conflict—as of oil and water. In Madhusudan these two discordances were distinct and quite marked. It was in the works of Bankim that a true synthesis commenced. Still, on the whole, the artistic creation of that age was something like putting on a dhoti with its play of creases and folds, and over it a streamlined coat and waistcoat and necktie. Both the fashions are beautiful and graceful in their own way. But there is no harmony and synthesis in their combination. It was Tagore’s genius that brought about a beautiful harmony between the two worlds. In the creation of the artistic taste of Bengal he has opened wide the doors of her consciousness so that the free air from abroad may have full play and all parochialism blown away. Yet she has not fallen a prey to foreign ways to become a mere imitation or a distant echo; it is the vast and the universal that has entered. True, Tagore’s genius belonged intimately to Bengal, but not exclusively; for it has been claimed also by humanity at large as its own. The poet’s consciousness has returned home after a world-tour, as it were. It has become the Bengali consciousness in a wider and deeper sense. So the poet sings:

My own clime I find in every clime,

And I shall win it from everywhere.

Thus, for example, the ideas and movements that have taken shape in Swinburne and Maeterlinck have induced some echoing waves in the works of Tagore here and there. Some of the things specially characteristic of the West, were fused into his inspiration, became his own and formed part of the being of the pure Bengali race: these have grown now its permanent assets. Rabindranath’s experience has, so to say, travelled across space to embrace the universe. On the other side, in the matter of time too his experience has far exceeded the present to climb to the lofty past. At times he soared high to the experiences of the seers of the Upanishads or the Vaishnava devotees, and came down with them into the widely extended domain of universal experience. The modernism of his poetic creation, developed on the wings of these two aspects, and its keynote is the harmony and synthesis of the East and the West, the present and the past. Thus the oriental and the occidental thoughts, ideas, experiences and realisations of the present and of by-gone times, that possess any value or special significance, have combined and are fused in the delightful comprehension of the poet giving birth to a new creation in which a great diversity vibrating in a common symphony blossomed with immaculate beauty.

How the two original streams of thought, oriental and occidental, were synthesised in Tagore’s work is a subject that demands a deep study. I do not propose to deal with the subject in its entirety, but I shall try to point out a few salient features. The European consciousness, especially modern, is centred on this physical world, this living body endowed with the ardent senses, on the undeniable reality of the outside world where, after all, things are transitory; and of the dualistic life it espouses, this consciousness lays more stress on death than on life, on misery than on happiness, on shadow than on light; it seeks beauty and fulfilment in contrast and conflict in human life and consciousness. Inspired by this idea our poet sings:

Not for me liberation through renunciation.

Or,

Is the Vaishnava’s song only for Vaikuntha?

Again,

Where is the light, O where? Kindle it with the fire of separation.

I do not say the indulgence of the lower nature, the physical propensities and the sense-objects is less prevalent in our country. The teeming wealth of sensuality that is found in Kalidasa and Jayadeva has hardly any parallel in the literature of any other country. But the oriental approach is quite different from the occidental. The consciousness and the attitude with which Europe has accepted and embraced the sense-world or the material world are profane, pagan—the enjoyment of pleasure in the grossest and the most materialistic way, pleasure for the sake of pleasure. The fount of tears pent up in the core of every transient object (“sunt lacrymae rerum”), so said Virgil, the great poet of Europe. The artistic mind of Europe derives its inspiration from there. The Indian consciousness even after accepting the material objects could not completely exhaust itself in the earthly relation only. As the Upanishad says, the husband, the wife or the son is dear to us not because of their own sake but for the delight of one’s soul. It is not that the spiritual basis of consciousness is directly or actively manifest in all Indians or even all creative artists of India. But this perception permeates the atmosphere, the firmament, the air, land and water of India. And this idea, on the whole, brought about a special outlook and tone in the style of her creative arts. The works of Vaishnava poets are replete with earthly love, at places only nominally associated with God; and yet even this nominal or tacit association is a very characteristic and special feature. And it cannot be put in the category of mere earthly and human outlook as known to us. At least earthly things and sense-objects have not been presented solely with their own norms and values. They have been assessed in relation to the values of something else, their truth has been determined as a help or an impediment to some other truth. Not that artists of this type are totally absent in Europe. There also—although it is the exception rather than the rule as here—we come across a few who have the experience of the Imperishable in the perishable, and the realisation of Consciousness in Matter. The experience of silence, for example, was in some so overwhelming as to render names and forms secondary—insignificant—and to reduce them to mere shadows. Thus to Wordsworth all natural truths and beauty are inherent in the power that presides over Nature which he calls Spirit.

Tagore wanted to seize the object as a real object and touch the body physically, with the sense of touch. Unlike the spiritual seers he could not remain content with embracing the object in and through the soul alone and the person through the impersonal. As a mortal he sought to taste the delight of mortal things. And yet he established the Immortal in the mortal. He looked upon the body as body and yet was united with it in and through something of the formless soul. The uniqueness of his realisation consists in the synthesis of the duality, the contrary. Like the pagan he maintained intact the terrestrial enjoying, even made it more intense, yet he brought down into it something of the supra-physical. And for this harmonisation he resorted to the consciousness of the Upanishads which is innate to his country. The thing that has bridged the gulf between the physical and the supra-physical, between the body and the soul, between the inmost within and the outmost without is the heart of the devotee—the emotional fervour of the Vaishnavas, adorers, lovers and those who have the fine sense of beauty and delight.

Rabindranath has the intuition of the Brahman, the infinite Bliss, the One without a second, which is beyond all limits and is the support of all, as the vital principle. He has, at every step, sung the victory and glory of this vital aspect of the Brahman. He has often cited this aphorism of the Upanishad:

All created things are moved by the pranic power.

Inspired by this idea he too had sung:

Deep I dive into the ocean of life

and breathe it in to my heart’s content.

The rhythm of life flowed out into movement and dynamism. Here again another feature of the modern mentality, characteristic, for example, of the vitalists, is found in him. But the difference is that he has not assigned the highest place to it, though he has emphasised it considerably. He has endeavoured to posit something of immobility within or behind the moving and to make all stirrings terminate in a wide peace. Although he gave himself to the duality, the many, the swirling flood-tide of the external world, he was in close touch with the inner being, the profundity which is filled with the calm and silence of the One.

No doubt, he says:

Away with your meditation,

Away with your flower-offering,

Let your clothes get torn and soiled.

But what he meant to say is this:

Then you may rush out to the wide world

And remain unsullied

In the midst of the dust,

And walk about freely.

With all chains on the body;

Until that day dawns

Remain in the depths of your heart.

The life that was the object of Rabindranath’s worship was no other than the Brahman in Its aspect of Pranic Energy. On the one hand the sense of this Prana-Brahman impelled him towards the world as such and, on the other hand, a gesture and glimpse of the Transcendent Brahman served to give a poise and measure, cadence and contour to that Immeasurable Energy.

We lay so much stress on this aspect of Tagore, because herein lies the main secret of man’s modernity and his immediate future. What is required of man is to realise and establish the supra-physical even in the physical without losing the reality of the latter, to convert the supra-physical into the physical. Though the physical was not lost in oblivion, yet its own forms and ideas were brought under the pressure of the supra-physical and tinged with the colour of the same, so that it could be seen in a new light as an image of the supra-physical—such has been the trend of ancient spiritual tradition. But the modernity of to-day wants to keep the nature and the essence of the physical intact and, keeping its speciality unimpaired, endeavours to manifest the supra-physical in the physical. Man’s universal urge to-day finds expression in the immortal line of Tagore:

O Infinite, Thou dwellest in the finite.

We believe that the entire future of humanity depends on this line of spiritual practice and its realisation in this life. And in this respect Rabindranath the poet has almost become to us the seer Rabindranath

RABINDRANATH TAGORE AND MODERNISM PART 2

In the consciousness of the artist of the past each concept, each thought, each sentence or word appeared as a well-defined, separate entity. Artistic skill lay in harmonising the different and separate entities. The criterion of beauty in that age consisted in the proportionate, well-built formation of the constituents—a symmetry and balance. In the modern consciousness and experience nothing stands in its own uniqueness. The lines of demarcation between things have faded, are almost obliterated—no faculty or experience has its separate existence, everything enters into every other thing. In the consciousness and experience of men and in the sphere of artistic, taste there is now a unification and an assimilation just as men want to unite, irrespective of caste and creed and national or racial boundaries. We want to replace the ancient beauty of proportion by a complex system of sprung rhythm and a sport of irregularities and exceptions.

So we may say that the difference between the past and the present is something like the difference between melody and harmony. The ancients used to play as it were on a one-stringed lyre accompanied with a melodious song, or carried on a symphony comprising the same kind of melodies. The moderns like polyphonic movements, conglomerations of many heterogeneous sounds.

From this standpoint it will be no exaggeration to say that Rabindranath Tagore has modernised the Bengalis and Bengali literature and the Bengali heart. Madhusudan brought in Blank Verse. But still his metre was based on the unit of word. By creating and introducing the metre of stresses Tagore brought about a speciality in modernism. In words, rhythms and concepts he has brought in a freedom of movement and swing, a richer, wider and subtler synthesis and beauty.

A poet of the olden times sings:

Who says the autumnal full moon can be compared to her face?

A myriad moons are lying there on her toe-nails.

Or take the famous line that received ample praise from Bankim Chandra—

The fair lady leaves, imparting overwhelming pangs of separation.

How far away have we come when we listen to the following lines of Tagore:

“Who art thou that comest to me, O merciful one?”

Asks the woman. The mendicant replies,

“The destined hour is come to-night.”

Or,

Thy feet are tinged red with the heart’s blood of the three worlds,

O Thou, who hast left thy hung-down plait uncovered,

Thou hast placed thy nimble feet on the central part

Of the bloomed lotus of world-desires.

After sharpening and heightening the intellect by the urge of inspiration, after magnifying and diversifying his imagination by the intellect infused with the delight of the inner soul, Rabindranath’s experiences at different levels of consciousness synthesised them all in a free and vivacious metre embodied in waves of poetry. He created a Utopia in which the modern world with all its hopes, aspirations and dreams has found the reflection of its own deeper nature.

The sweetness, skill and power of expression that are found in the Bengali literature of today were merely an ideal before Tagore bodied them forth. We, the moderns, who are drawing upon the wealth amassed by him for over half a century and we who are using it according to our capacity often think that it is the outcome of our own genius.

We are swept by the giant billow caused by Tagore. But being placed at the crest of it we can hardly conceive how far we have come up. Again forgetting all about the wave we claim all the credit for ourselves. One of the signs of the rich and mature language is that every writer has at his command a ready-made tool of which he has to know only the proper manipulation. In the literature of that language no writer falls below a particular standard or a level of tune. The writer, who imbibes the genius of a language, and literature and its ways of expression, is carried on by them in spite of himself. Of course, we do not claim that Bengali literature has already reached the acme of perfection. But the growth and the development amounting to a full-fledged youth have been the contribution solely of Rabindranath. Again, in this respect his indirect thought-influence has far exceeded his direct contribution.

We have used the word “modern”. Now the question is whether the term “modern” should include the ultra-modern also. The ultra-moderns have gone one step forward. The movement of eternal youth and the overflow of youthful delight in Rabindranath are apt to march towards the ever-new, to commune with the novel, to accord a cordial welcome to the ever-green. There it is quite natural that he should have sympathy and good-will for the ultra-modern also. Nevertheless, it must be kept in view that above all he was the worshipper of the beautiful and of beautiful forms and appearances. However soft and pliant might have been the frame of his poetry, in the end it remained after all nothing other than a delicate shape of beauty. It is doubtful whether the ultra-moderns have retained anything like the frame-work of beauty. In fact, under their influence, the frame-work has not only got dissolved but also practically evaporated. Not to speak of rhyme, they have banished the regulated rhythm and pause. They have adopted a loud rhetoric and an over-decorated personal emphasis. If we want we may trace a reflection or have a glimpse of ultra-modernism in the following lines of Tagore’s Purabi and Balaka:

Behold, by what a blast of wind,

By what a stroke of music

The waters of my lake heave up in waves

To hold speechless communications between this bank and the other!

The mountain longs to become an aimless summer cloud.

The trees want to free themselves from their moorings in the earth

And to be on the wing and to proceed in pursuit of the sound

And become lost in their search for the farthest of the sky in a twinkling.

(Balaka)

But still here we do not come across the note of a reversal, dissolution, revolution. It seems the poet retains an inner link with the heart of the hoary past in spite of so much of his novelty and modernism. And he did not like to cut asunder that link.

This deep conservatism alone made Tagore the worshipper of symbols and did not allow him to be a revolutionary iconoclast. Indeed one can draw one’s attention to the speciality of his unique skilfulness. Many a time he held firm the structures and forms first in a sportive mood and then shaped them under strict restrictions. The play of bondage, freedom and lightness found more expression in his words, nay, more in his metres, still more in his concepts, and lastly his attitude far surpassed even his concepts. In connection with his delineation he gave expression to a unique softness and delicacy in the midst of firmness. He placed the formless soul in the inert body and brought the Infinite into the finite and gave us the taste of liberation amidst innumerable bondages. Further, in spite of close intimacy and familiarity, there is an aristocracy and glory in the manners and movements of his poetry; this too became a stumbling-block on the way of his becoming an ultra-modern.