It is a peculiar fact of human nature that the sweet and innocent ambitions of our childhood linger in our later years. Thus it is possible to find at the core of every great statesman or inventor or writer a desire to become something quite simple and ordinary. The greatest human being I have ever known is Sri Chinmoy. He was a spiritual guide, first and foremost, but within this calling he encompassed the roles of poet, artist, composer, musician and athlete. Given his vast accomplishments in each field, it is uniquely touching to discover that as a child his only longing was to work on trains.

In September 1992, one of many occasions when he mentioned this early ambition, he said, “I had a desire in my childhood to work on a train. My father was the chief inspector of the Assam-Bengal Railway Line. I thought, ‘Oh, if I can blow the whistle or wave the lamp, I will have the whole world!’ That was my desire.” 1

Almost two decades earlier, in 1974, he had written, “I used to want to become a ticket checker on a train. When I was a child and the ticket checker came by on the train and asked for the tickets, I was so fascinated by his movements and his gestures that I wanted to become just like him.” 2

At other times over the years, he spoke of wanting to follow in the footsteps of his father and be the conductor or driver of the train, always adding at the end of his reverie, “God did not see fit to fulfil this innocent desire of mine. Instead, God has given me a far more difficult job.” 3

Although Sri Chinmoy went on to become a source of boundless inspiration to spiritual aspirants the world over, he cherished his love of trains to the end. As he said in 1991, “trains are in the life-blood of our family.” 4

Madal’s Epic Train Journeys

Intercity express trains, local trains and subways are a way of life for millions of Indian commuters nowadays. However, train rides were a much-treasured rarity for the young Chinmoy (known then as Madal), largely because of the unique topography of East Bengal.

Madal’s occasional sorties from his village home in Shakpura to Chittagong town, where his father and elder brother worked, were made by ferry. Chittagong is the southernmost port of the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta – the world’s largest delta – stretching 354 km (220 miles) from West Bengal to East Bengal. Chittagong derives its name from Arab traders who called it ‘Shetgang’ (‘shet’ meaning delta and ‘gang’ meaning river). Chittagong district is, in fact, comprised of hundreds of small islands connected by a labyrinthine series of waterways. In and around his village of Shakpura, and also as far as his mother’s village of Kelishahar 9.6 km (6 miles) away, Madal moved about by foot or bullock cart.

And yet, despite his limited access to trains, by the time he was twelve years old, Madal had covered more than 22,500 km (14,000 miles) by rail. How did this striking paradox come about?

I believe it is possible to say, without exaggeration, that it was due to one momentous event in the Ghosh family: towards the end of 1932, Madal’s eldest brother, Hriday, left Chittagong and went to Pondicherry, South India, to join the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. He was at that time twenty-one or twenty-two years old and had just completed his B.A. at Chittagong College. His youngest brother, Madal, was just one year and three months old.

Hriday’s sudden decision to leave precipitated a family crisis. Two long weeks passed before the family discovered where he had gone. The second eldest brother, Chitta, later recorded in his notebook: “[Hriday] was a most brilliant student. My father was furious. He would not even look at our brother before he departed. Then my mother took an oath that she would fast unto death if my father did not bring her to the Ashram. It took two days for my mother to soften my father’s heart. At the end of two days, he surrendered to my mother. He brought my mother and my whole family to the Ashram.” 5

Somehow, Shashi Kumar Ghosh obtained extended leave from his job as chief inspector of the Assam-Bengal Railway and, in early 1933, the family set off en masse in Hriday’s footsteps to try to persuade him to return home. Although they were unsuccessful in this enterprise, they did become reconciled to his chosen path.

And so began what would become a regular pattern over the next eight years of trips to Pondicherry to visit Hriday. After that initial trip in early 1933, they undertook round trips in 1936, 1939 and 1941. Each round trip was of epic dimensions – 4,915 km (3,054 miles), the equivalent of the distance from Mumbai to Moscow. This distance included 315.6 km (196 miles) by steamer and ferry. And, from a close examination of the timetables listed in the Indian Bradshaw #803, October 1932, we can estimate that the journey took at least five days each way. The trip of 1936 took even longer and included approximately 500 additional kilometres (310 miles) because the family made a number of side trips to sacred places along the way.

These family processions between Chittagong and Pondicherry culminated in one final one-way trip in July 1944, after the passing of Madal’s mother and father. Hriday had taken permission to return to Chittagong for his mother’s last days. After her death, he wound up the family affairs and took the remaining members of the family with him to live at the Ashram.

Madal’s train experiences

In a book dedicated to his father and published in 1992 My Father Shashi Kumar Ghosh, Sri Chinmoy offers some charming insights into his experiences as a young boy travelling immense distances by rail:

“Because my father had been a train inspector, we could travel free all over India. Eleven human beings my father could take free: two servants, one cook and eight members of the family. I used to enjoy riding on the train so much. The trains were long, with many seats inside. In those days, they were not so crowded. Now they are very crowded; there is no room. Indian trains were like bullock carts – twenty to thirty miles per hour. My only ambition was to become a ticket collector or inspector like my father. He started out as an ordinary officer of the Assam-Bengal Railway. Then he became head inspector of the whole line. But God did not fulfil my desire. Whenever we went on the train, everybody in the family used to fall asleep during the trip, but I could not wait to see the next station. There people used to carry things on their heads, and they had a peculiar way of shouting, ‘Tea! Betel nut! Ancient Indian cigarettes! Real cigarettes!’ and other things. My mother, brothers and sisters all used to sleep, but there was no sleep for me!” 6

Timetable of Trains from Chittagong to Pondicherry

Just how the family negotiated these long trips to and from Pondicherry is fascinating. It is also a tribute to Shashi Kumar Ghosh’s expertise and familiarity with the intricate workings of the Indian railway system, which is the largest in the world. I am greatly indebted to R. Sivaramakrishnan of Pondicherry, who is a member of the Indian Railways Fan Club Association (IRFCA), for giving me a glimpse into this era of Indian train travel and for so kindly providing me with the following information.

STAGE ONE: Shakpura to Chittagong

| Transit time: 1½ hours | Mode of transport: river ferry | Distance: 13 km (8 miles) |

Making Ticket Reservations in Chittagong Shashi Kumar Ghosh would have had to make reservations for the train journey around a week in advance in order for the issuing station to get telegraphic confirmation of the onward reservations from the changing stations. Tickets were booked and issued manually, with the booking clerk taking up to ten minutes to issue a set of tickets, and considerably longer if more than one train was involved. The large size of the Ghosh party would have complicated the booking process even further, even though they were travelling free of charge.

Because of Shashi Kumar Ghosh’s high-ranking position with the railway, we may presume that the family members were entitled to travel first class, while the two servants most probably travelled third class. The first class fare up to Calcutta, inclusive of the steamer, was 51-1-6 (51 rupees, 1 anna, 6 paise). The third class fare was 6-15-6 in October 1932.

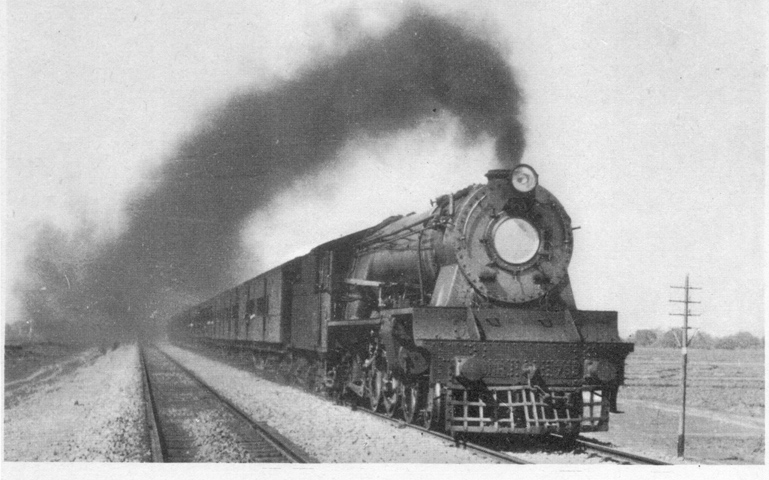

A typical M class steam locomotive in use in the 1930's and 40's.

Photo credit: Shaw Webspace

There was one daily train from Chittagong towards Sealdah Station in Calcutta. It was called the Chittagong Mail and it ran on a metre gauge track up to Chandpur.

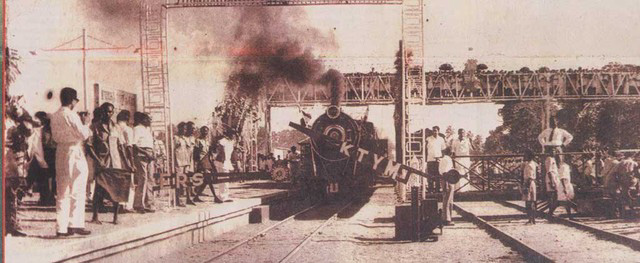

Chittagong Railway Station

Photo credit: Jay Davidson

STAGE TWO: Chittagong to Calcutta (23 hours)

| 2100 hours | Depart Chittagong | #3 Chittagong Mail |

|

MG – ABR (Metre Gauge/Assam Bengal Railway)

|

||

| 0153 hours | Arrive Laksam Junction | Mileage total: 81 (130 km) |

| O223 hours | Depart Laksam Junction | |

| 0350 hours | Arrive Chandpur | Mileage total: 113 (182 km) |

At Chandpur, in the small hours of the morning, the passengers would disembark with their luggage and board a steamer for the picturesque 95-mile (153 km) trip north-west along the Ganges (known as the Meghna and Padma in different sections of its course) to Goalundo Ghat. There they would board the broad gauge counterpart of the Mail which would take them to Sealdah.

| 0430 hours | Depart by steamer | |

| 1400 hours | Arrive Goalundo Ghat | Mileage total: 208 (335 km) |

A steamer approaches the Goalundo Ghat

Photo credit: Great Mirror

| 1440 hours | Depart Goalundo Ghat | #6 Chittagong Mail |

|

BG – EBR (Broad Gauge/East Bengal Railway)

|

||

| 2000 hours | Arrive Calcutta (Sealdah) | Mileage total: 363 (584 km) |

Metre gauge (MG) referred to rails that were 1,000 mm (3 ft 3⅜ in) apart, while broad gauge tracks (BG) were 1,676 mm (5 ft 6 in) apart.

Overnight in Calcutta

By this stage, the family would have covered 584 km (363 miles) over a period of a day and a half (not including time spent in Chittagong), travelling by small ferry, large steamer and two different types of steam locomotive. If the Chittagong Mail was running on time, they would have pulled into Sealdah Station, Calcutta, at eight o’clock in the evening. The daily Mail Train to Madras would have left from Howrah Station, across the Hooghly River and on the other side of the city, just an hour earlier. So the family would have had to spend one night and almost a full day in Calcutta before catching the next day’s Madras Mail. Mr. Sivaramakrishnan suggests that the family may have crossed to Howrah Station for the night. Howrah had spacious waiting rooms for the upper classes as well as retiring rooms, and a waiting hall for class III passengers with baths. He adds, “Most passengers preferred to stay in them for 12 to 24 hours for a connecting train, rather than going out of the station to find a lodge.” 7 Since Howrah Bridge was not finished until 1943, passengers crossed between the two termini – Sealdah on the east bank and Howrah on the west bank – by means of a bridge of boats.

Howrah Station, Calcutta circa 1928

Photo credit: Mrinal, Indian Railway Fan Club Association

The passenger concourse at Howrah Station, 1943

Photo credit: Mrinal, Indian Railway Fan Club Association

STAGE THREE: Calcutta to Madras (37 hours 10 minutes)

| 1900 hours | Depart Howrah | # 4 Madras Mail |

|

BG – BNR (Broad Gauge/Bengal Nagpur Railway)

|

||

| 1415 hours | Arrive Waltair (now Visakhapatnam) | Mileage total: 547 (880 km) |

| 1435 hours | Depart Waltair | #2 Calcutta Mail |

|

BG – M&SM Rly (Broad Gauge/Madras & Southern Mahratta Railway)

|

||

| 2310 hours | Arrive Bezwada | Mileage total: 764 (1229 km) |

| 2330 hours | Depart Bezwada | |

| O810 hours | Arrive Madras Central | Mileage total: 1032 (1660 km) |

Transfer in Madras

Arriving in Madras in 1933, a totally unfamiliar city, after almost four days of travelling, with young children in tow, a wife who was frail from fasting, and the added problems of luggage to deal with and food to procure, it is quite possible that Shashi Kumar Ghosh and his party failed to make the next available connection to Pondicherry, which was the #7 Dhanushkodi Express at 1115 hours. Moreover, they would have had to transfer to Madras Egmore Station, almost a mile from Madras Central, which would have involved hiring several rickshaws to convey the whole party. One assumes that the family transferred to Egmore Station, installed themselves in the spacious waiting room, confirmed their onward tickets, purchased some food and rested. Depending on the time of year they were travelling, they may have encountered scorching temperatures in the 40's, and extremely high humidity.

The fanciful exterior of Egmore Railway Station, Madras

Photo credit: K. Pichumani/The Hindu

STAGE FOUR: Madras to Pondicherry (6 hrs 25 mins or 7 hrs 40 mins) Mr. Sivaramakrishnan presents two possible timetables here. Assuming they made the transfer from Madras Central to Madras Egmore on time, the connection would have been as follows:

| 1115 hours | Depart Madras Egmore | #7 Dhanushkodi Express |

|

MG – SIR (Metre Gauge/South Indian Railway)

|

||

| 1540 hours | Arrive Villupuram Junction | Mileage total: 99 (159 km) |

| 1600 hours | Depart Villupuram Jn. | #247 Passenger train |

| 1740 hours | Arrive Pondicherry | Mileage total: 123 (198 km) |

Alternatively, perhaps not wishing to arrive in the evening, they would have waited in Madras for the day and caught the following evening train:

| 2130 hours | Depart Madras Egmore | #9 Trivandrum Fast Passenger |

| 0150 hours | Arrive Villupuram Junction | |

| 0345 hours | Depart Villupuram Jn. | #241 Passenger Train |

| 0510 hours | Arrive Pondicherry |

The stately Pondicherry Railway Station

Photo credit: blob59 on flickr.com

| A metre gauge steam locomotive pulling into a station in Cochin. Although this is not the exact train that was used on the South Indian Railway, it does convey something of the atmosphere and experience of the platform, the station attendants holding coloured flags with which they gave semaphore signals, the waiting passengers, and the massive blasts of steam upon arrival. Photo credit: Indian Railway Fan Club Association, Krishnan Nair Studio, Ernakulam and Mr. Gopalkrishnan

|

Those who are interested, advises Mr. Sivaramakrishnan, can also trace the journey visually by turning to Volume 26 of The Imperial Gazetteer of India, Atlas 1931 edition, Railways and Inland Navigation, pages 25 and 26. These excellent maps can be found at the following links: Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 26, Atlas 1931 edition, Railways & Inland Navigation, p. 25. and Railways & Inland Navigation, p. 26.

The trip of 1936

In 1936, when Shashi Kumar Ghosh made his second trip to the Sri Aurobindo Ashram with his wife and children to visit his eldest son, Hriday, and to seek the blessings of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, he decided to visit many temples and holy places along the way. These places of pilgrimage had been sanctified by spiritual Masters, such as Sri Chaitanya, Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda. Others were consecrated to Lord Shiva and other Hindu Gods. Madal would only have been five years old at the time, too young perhaps to take in the details of the trip, but his next older brother, Mantu, who was eight, retained vivid memories of this journey. From Mantu’s recollections, published in his book My Heart-Songs, we can reconstruct the general route their annual pilgrimage took that year:

“In 1936 our mother, father, Chitta-da, Chinmoy and our sisters and I travelled to Navadwip, the birthplace of Sri Chaitanya. There we saw a statue of the golden Gauranga. I still remember the kirtans that were sung there. Men were wearing women’s clothes and singing kirtans. They were singing devotional love songs.

From there we came to Dakshineswar, the sanctified abode of Sri Ramakrishna. After visiting the temples, we continued on to Belur Math which had been established by Swami Vivekananda. Afterwards, we went to see the zoo, the museum and the Victoria Memorial in Calcutta.

Leaving Calcutta, we journeyed to Burdaman to visit our uncle. He was a great Vaishnava devotee. There, too, we heard kirtans. Inside the village, we sought out our uncle at his Guru’s Ashram. It was in the midst of a beautiful garden. Sri Chaitanya also came to Burdaman during his wanderings. There he met with Keshab Bharati, a renowned scholar. We also visited the home of Madhai, the ruffian who became Sri Chaitanya’s devotee. Here there is a special bathing ghat.

From Burdaman we travelled to Orissa and visited the world famous temple of Jagannatha at Puri. We received prasad from the temple.

Continuing southwards, we visited many temples on our way. Some of the temples, we even visited at night. In front of the statues, countless little, little lamps were burning. We could not see the deities properly and there were hundreds of bats moving around overhead. In front of one temple there were two large pillars. We heard that they were golden palm trees.

Next we went to Prahllad Puri. There we saw mountains and the ocean where Lord Vishnu killed Hiranya Kashipu, Prahllad’s father. We have seen everything. From there we went to Pakshi-Tirtha, the place of bird pilgrimage. Thousands of birds make their home there. We came a long way. We saw a Brahmin on top of a mountain. He was eating. Two white birds came and took food from his hands and then left.

Then we went to visit the sacred Venkateswara temple. The temple is situated on Tirupati Hill. It is one of the most famous temples in South India. It is in Andhra State. Nowadays the bus can come right up to the temple. Formerly, it was not so easy. One had to come up to the temple by covering a very long distance. People used palanquins because of the high elevation.

There were many monkeys in the vicinity of the temple. Our father was eating a mango. One monkey took away his mango and gave our father a slap. Chinmoy, Chitta-da and I did not go inside the temple. Our mother had to come down and see Chinmoy.

From here we came to the Sri Aurobindo Ashram for Sri Aurobindo’s and the Divine Mother’s Blessings.” 8 – Manoranjan (Mantu) Ghosh

This journey involved many detours, side trips and stops along the eastern coastline, adding hundreds of kilometres to the journey. A number of these sacred places of pilgrimage, such as Navadwip, were not directly accessible by train. In other places, it would have been more practical to take a ferry. A river ferry from Navadwip, for example, going south on the Hooghly (Ganges) River would have been the ideal way to stop at Dakshineswar and then at Belur Math on the opposite bank. The distance from Navadwip to Calcutta is 94 km (58.4 miles).

After a day or two seeing various sights in Calcutta, it seems the family may have boarded a train on the Eastern Railway Line for the 100 km trip to Burdaman (also known as Burdwan or Bardhaman) to the north/west of Calcutta. Some of the other places mentioned, such as Prahllad Puri, were particularly remote, while the visit to Venkateswara Temple on Tirupati Hill involved considerable physical effort – climbing 14 km up more than 4,000 steps – an endeavour that seemed to have proved too much for the youngest son, as Mantu notes, significantly, “Our mother had to come down and see Chinmoy.” 9

Indelible Train Experiences

Although these epic train journeys all took place between 1933 and 1944, the exhilarating experiences of those endless days – running from side to side in the carriage to view the passing scenery, observing golden fields utterly different from the rich green rice paddies of his native East Bengal, anticipating the ever-changing Coromandel coastline, alighting at little stations to buy snacks, listening to the sound of the majestic wheels churning, watching the chaotic activity on the platforms as people surged on and off the train, falling asleep to the gentle rhythmic swaying of the carriage – all these experiences passing through the consciousness of the young boy were, indeed, indelible.

On one occasion, the young Chinmoy observed a most curious incident. He writes, “I was watching at the train station when it happened. I saw a sadhu, a thin fellow, an old man of sixty years. He was insulted because a policeman had thrown his stick out of the train. The sadhu had come out of the train and was standing on the platform, very, very furious, and staring at the engineers. There were two engineers; one was the main engineer and the other was his assistant. The sadhu entered into the brain of the chief engineer and made him incapable of operating the train.” 10

By and large, however, we can see that Sri Chinmoy internalised his early train experiences. His mature writings focus on inner realities rather than autobiographical details. And yet a constant train motif can be traced in his writings, most especially in his poems. He uses the image of the train not only to make abstract spiritual concepts relevant to our day and age, but to impart a dramatic urgency to his message:

“A restless mind

Is nothing but

A runaway train

That courts destruction.” 11

“If your dedication is not nourished

By faith every day,

Doubt may at any moment

Derail your dedication-train.” 12

In other poems, he hints at the charm of the train journey itself:

“Singing a song soulfully

Is exactly the same

As enjoying a ride on an express train:

Panoramic views on either side.” 13

“Fastest runs to the Goal Supreme

My Lord’s Love-Train.

Singing and dancing, therein my breath –

No bondage-chain.” 14

The following poem seems to encapsulate the symbolic meaning of his train experiences:

“An express train

Of consecutive great ideas

Has brought me to my Himalayan goal:

The sleepless service of humanity.” 15

And, in the light of Sri Chinmoy’s recent passing, his explanation of the passage of death in terms of a train ride is especially poignant:

“We are all like passengers on a single train. The destination has come for one particular passenger. He has to get off at this stop, but we still have to go on and cover more distance.” 16

An Innocent Childhood desire fulfilled at last

As an Australian, I feel a special connection to Sri Chinmoy’s love of trains because it was here in our country that he was able to fulfil at last his childhood desire to drive a train. This event took place at the famous “Puffing Billy” heritage railway in Victoria on September 13th, 1984 – when Sri Chinmoy was 53 years old. Recounting his experience afterwards, Sri Chinmoy made the following unforgettable statements:

“Since my childhood ended, in my entire incarnation I have had only two or three happy moments. Of course, when I achieved God-realisation was one. And the day I rode with the engineer of the steam train in Australia was another. When I was young, it was my greatest desire to be the driver of a train. God did not see fit to fulfil this innocent desire of mine, but now my Australian children have fulfilled it!

|

|

Sri Chinmoy on “Puffing Billy” in the Dandenong Range, Victoria, September 13th, 1984. Photo credit: Sri Chinmoy Centre

|

“The engineer was so kind, so nice; he received so much. Every two minutes he was putting coal in the furnace, and talking, talking, talking, all about his experiences with this train and other trains. He has been in India, and he talked about the Darjeeling train, which is much more peculiar and dangerous than this one. This train is mainly for children and for tourists, and quite a few of the workers on it work for free. His real job is running a nursery, and driving the train is a labour of love. If everyone took a salary, they would not be able to keep the train running.

“Every year there is a race – the train versus runners. The runners start and finish at the same place as the train. But they run on the road, while the train goes on its track. The route is very hilly and very scenic… The driver told me, ‘We get joy by losing to the runners. Otherwise, could anybody defeat us?’ The train can safely go about 22 miles per hour. If it goes much faster, it will go off the rails.

“At one point the engineer asked me to sit on his seat, but it was so narrow! My thigh was larger than the seat. The sound the train made gave me such joy. And the whistle was so loud! He would pull the handle just half an inch, and such a loud noise it made!

“So my Australia has given me tremendous joy by fulfilling an innocent childhood desire of mine.” 17

– End –

Copyright © 2009, Vidagdha Bennett. All rights reserved under Creative Commons license.

Endnotes:

1 Excerpt from Sri Chinmoy Answers, Part 19.

2 Excerpt from God’s New Philosophy.

3 Excerpt from The World-Experience-Tree-Climber, Part 4.

4 Excerpt from To The Streaming Tears Of My Mother's Heart And To The Brimming Smiles Of My Mother's Soul.

6 Excerpt from My Father Shashi Kumar Ghosh.

8 Excerpt from My Heart-Songs.

10 Excerpt from The Astral Journey.

11 Poem no. 21,296 from Seventy-Seven Thousand Service-Trees, Part 22.

12 Poem no. 14,457 from Twenty-Seven Thousand Aspiration-Plants, Part 145.

13 Poem no. 5,776 from Ten Thousand Flower-Flames, Part 58.

14 Poem no. 7 from My Silence-Heart Blossoms, Part 1.

15 Poem no. 6,813 from Ten Thousand Flower-Flames, Part 69.

16 Excerpt from Death and Reincarnation.

17 Excerpt from The World-Experience-Tree-Climber, Part 3.